Mentors

- Nisarg Joshi

- Arpitha Raghunandan

Members

- Aditya Sohoni

- Suhas K S

- Praveen

Introduction

Tor which stands for The Onion Routing protocol is commonly associated with the dark web and thought of as some browser that can hide your activity and help you connect to this deeper layer of the web. Well, it’s not entirely wrong as a description but that is just a very surface-level understanding of Tor. This blog post will try to get in technical depth and try to break down Tor’s inner workings and how you can too design and implement Tor just like we did as a part of this project.

TOR as a Protocol

Tor, which stands for The onion router or The onion routing protocol, is simply that - a Protocol. It’s simply a network protocol just like HTTP or FTP or something similar that enables communication between hosts and has various properties.

The world of networking is full of protocols and layers and it’s easy to get lost in this. Hence we assume a basic understanding of networking and communication, knowing basics like the OSI model, TCP/IP stack and basic concepts.

So Tor being just a protocol works at the application layer like HTTP. Hence it is not part of the kernel-level network stack and can be easily implemented if we know the specification of the protocol. Every protocol is designed with certain properties in mind, in the same way, Tor is designed with following in mind:

- It is supposed to operate as a network overlay protocol. This means it is supposed to form an overlay network on top of existing network traffic which can use any application layer protocol underneath(like HTTP, FTP, SSH and so on)

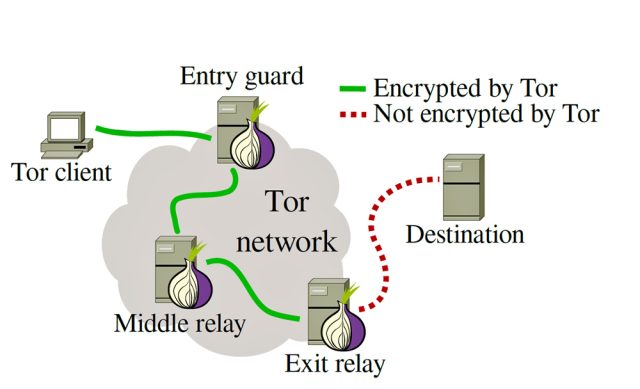

- It operates over a network of nodes and creates virtual circuits through this tor network which allow routing of traffic through the virtual circuits

- Through its design of virtual circuits and use of cryptographic protocols, it helps in creating secure channels of information transmission that gives the tor network the lucrative anonymity that it promises. Hence it is designed for anonymous transfer of data between client and end host.

We will deconstruct how Tor works and achieves these properties and how all this ties to the dark web and hidden onion services.

TOR: Components that make it work

From a design point of view, tor protocol has 3 parties involved:

- The Tor Client which we call the Onion Proxy

- The Tor Router which is also called Onion Router.

- The End Host/Destination

- The Tor message which is also called the Tor Cell

Tor Client/Onion Proxy

The onion proxy is the piece of Tor component that runs as a part of the Tor browser that you download. It facilitates any client to connect to the dark web and access the overlay network operated by Tor. The Proxy component takes your vanilla HTTP traffic(for example) and wraps it into Tor traffic and sends it across the Tor network for anonymous communication. For you, as a client, it still feels like any other normal browsing experience.

The reason why it is called a proxy is that it behaves as a proxy to your normal web traffic communication. It actually is a SOCKS proxy and operates at the SOCKS layer(but let’s not get into this detail).

The onion proxy is also the one that builds a virtual circuit for communication, sets up the circuit and starts the transmission of data back and forth. This virtual circuit is created on the Tor network using the next component we will talk about which are the Tor routers/onion routers.

Tor router/Onion Router

This part of the tor protocol is the heart of the overlay network that Tor creates for communication. When you download the Tor Browser, you have an option to configure yourself as a Tor Node, which is precisely the onion router. The onion router is the process which makes your machine/host act as a router in the tor network. If you chose to run your machine as a Tor node, then you are permitting Tor to use your machine as a part of the overlay network that Tor creates.

What routers do is participate in the virtual circuit creation which some onion proxy somewhere in the world has created. And then route the traffic through themselves in the circuits which they are a part of. An Onion router can be part of multiple circuits, it maintains a routing table sort of a thing that allows it to route the traffic through correct circuits.

Hence you can be a proxy as well as a router at any given point of time. Also, there is a special kind of node called the exit node which is the last node in the virtual circuit. This node is special in the sense that you can choose not to be the exit node because it is exposed directly to the outside internet and has some serious security implications. (For example, if some anonymous clients are buying drugs over the Tor network it will seem like the exit node is making the requests. So beware before you choose to be an exit node)

End Host/Destination

This is as the name suggests the actual host the client wants to connect to. It can be a plain internet end host or it could be a hidden service. (We will not cover hidden services for simplicity). Not much to dig here.

Now knowing the major components lets breakdown how the protocol actually operates and how it creates a secure anonymous channel/circuit using cryptography and other tools.

Tor Message/Cell

Every network protocol in the networking world has a message format, which is used for consistent communication with the clients and servers using that protocol. A message format definition is half the work done for the given protocol design. The only thing then left is designing the processing of those messages.

In the same manner, Tor has a message format that encapsulates all the traffic moving through the virtual circuits. It is called Cell. Any basic unit of message/communication is carried inside a Tor Cell. Now the Cell has multiple formats based on the type of traffic being carried which you can discover more in the spec of Tor(will link it in the resources for this post).

A few points about the Tor Cell:

- It is originally proposed as fixed size with 512 bytes sized messages.

- It has a header and a payload(as expected duh!)

- There are 2 major cell types: control cells and relay cells

- Control cells help in circuit creation and teardown etc.

- Relay cells carry the actual data, like HTTP data wrapped inside themselves.

Tor: Design of Circuits and Data Transmission

Having looked at the components that build this protocol, we will look at how it actually works, step by step. Here we go:

Having looked at the components that build this protocol, we will look at how it actually works, step by step. Here we go:

- First, the Onion Proxy process running on a client machine starts by creating a circuit. A circuit is simply a connection between a set of onion routers.

- To create a circuit, it starts by picking 3 nodes out of an open public directory listing of these routers. The routers are listed publicly and it selects 3 at random to create a single circuit. (Minor detail: It takes care of assigning exit node based on the policy set by the node)

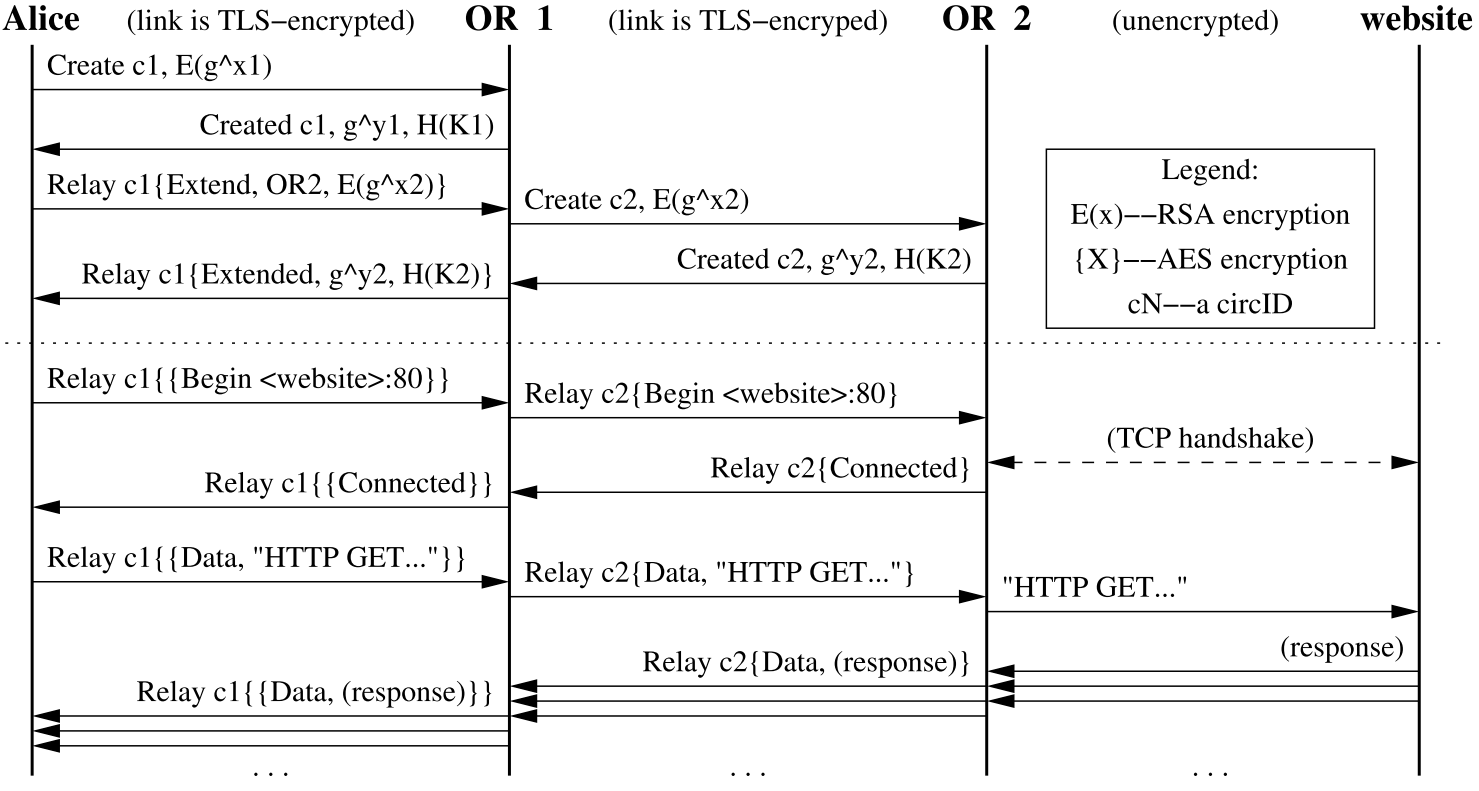

- The circuit creation is a crucial step as we will break it down here:

- The circuit is created incrementally

- The proxy first talks to the first node in the circuit over a TCP socket connection. This connection is secured using TLS at the transport layer. (Implicit assumption: these nodes have a set of cryptographic keys that enable encryption of traffic). In this communication, the onion proxy establishes a session key that it will use in encrypting the data at Tor layer along the circuit. This crypto key is established using Diffie Hellman(DH) key exchange. The Proxy does this using a control cell called CREATE Cell

- Next, it sends an EXTEND cell to the first node whose payload has DH key exchange information. The first node sends a created cell by copying the extend cell payload to the next node. The extend cell has information like the IP address to connect to the next node. The 2nd router responds with “CREATED Cell” and the 1st node sends back an EXTENDED Cell. In this transaction, the DH key is established between the second node and the proxy, the first node does not have this particular key.

- Next, similarly, the circuit is extended to the exit node. This way each node holds a separate DH session key with the onion proxy, not known to anyone else on the network. This way the traffic can be encrypted for each hop in the circuit. Part of this provides security and the coveted anonymity. All the cells mentioned in this section are called control cells.

- After the circuit is created, the proxy is ready to take any data along the circuit. The circuit has a concept of streams that allow multiple TCP connections to different end hosts on the internet to be made via the same circuit. Each Relay Data Cell carries a stream ID to identify the TCP connection. We will consider without loss of generality a single stream inside a circuit. Let’s see how data is sent to the end host and also how it provides anonymity:

- First, the client types a URL in the browser, skipping the DNS resolution, let us assume an HTTP GET request is made to the website(end-host). This HTTP GET request is wrapped inside a Relay Data Cell payload.

- This payload is encrypted in 3 layers with the 3 session keys of the nodes on the circuit. Then it is sent to the first node. We will note here that the onion proxy maintains only a single TCP connection to the first node which in turn is connected to the next node and so on.

- The first node receiving the cell will look at the circuit ID, stream ID etc to decide routing information. It will decrypt the cell and if the checksum matches the checksum of payload, that means the cell has been fully decrypted. If not, then it forwards the cell to the next hop.

- At next-hop again the same process happens and a layer of encryption is removed. So at each hop like a layer of onion, encryption is removed using the pre-established session key of that router with the proxy on that circuit. This is where the protocol gets the name onion routing.

- At the last hop, the cell is fully decrypted, the exit node takes the HTTP GET Payload and makes a TCP connection to the end host mentioned in the message and connects to it. It sends the HTTP message on behalf of the client.

- Here we can observe how anonymity is preserved. The end host does not know who the actual client is since it only sees the exit node that is connected to it. Also, the exit node does not know the actual client proxy since it got the circuit creation from the previous hop. The previous-hop also does not know the actual client. Now the first hop does know the actual client, but it does not know the end host or the exit node, so it does not know the destination. Hence this way no one except the client has full view of the communication in the circuit. All this jugglery provides the anonymity that Tor promises. Of course someone with the full view of the network can break it, but that requires serious resources to control all the nodes in the Tor network. Also a small point to note, a circuit of a single node and 2 nodes are not useful, we need 3 or more nodes. A single node is simply a proxy. Using more than 3 nodes will slow down the process of getting a response.

- Now let’s move onto the response sent back from the end host:

- The HTTP response is sent to the exit node, which rolls up the response into a relay cell and encrypts it and sends it to the previous hop.

- The previous hop simply encrypts the cell and passes it towards the proxy along the circuit. Thus each hop encrypts the response with the session key and sends it to the proxy.

- The proxy decrypts all the 3 layers sequentially and gets the original payload and passes it to the HTTP client that started the request. This completes only round trip communication over a Tor circuit.

TOR: Implementation Details

Designing any network protocol needs you to implement a message format creator and parser. This is 50% work done. Then the rest is writing sockets that will send and receive these cells and process them. Although it’s not trivial to design a high-performance socket application since that needs the usage of good amount multithreading and non-blocking async processing prowess, a toy project does not need that.

In this project, we did something similar. We divided our work into three sections:

- Cell Parsing and Processing

- Onion Proxy implementation

- Onion Router implementation

For the project, we used python mainly for its amazing socket and cryptographic support. Although one shortcoming compared to C/C++ we could see was, how easily C can play with bits and bytes which makes it ideal for packet parsing. We took this trade-off for the ease of coding and higher level constructs that python provides.

We followed an object oriented approach with practices like decoupling modules and software components. For Cell we implemented python classes that represent cell types. We wrote lower level cell parsing and processing functions as a part of the Cell module itself, which will be called upon by the higher level proxy and router modules. We also created serializers and deserializers to convert the python Cell Objects back and forth to bytes which can be used to send down the sockets. We used the “struct” library from python to achieve it.

Other modules were onion proxy and router that create circuits and send and receive cells and process them using the lower-level cell processing and parsing primitives mentioned before.

The entire code is open source at: https://github.com/IEEE-NITK/tor_project

We followed the Tor Spec and Tor Design paper to implement the protocol. These are linked in the resources section below.