Mentors

- Krithik Vaidya

- Suhas K S

- Vineeth R

Members

- Adithya Chandrassery

- Jason Krithik Kumar

- Rakshita Varadarajan

Introduction

This project was undertaken as a learning experience, to understand the challenges involved in building distributed systems and to explore important ideas in the field such as consistency, consensus, replication, fault tolerance, etc. Our primary goal was to implement a distributed key-value store providing linearizable consistency using the Raft consensus algorithm. We then built upon it to create a (simplified) DNS service in the cloud.

Distributed Systems

Distributed systems involve a set of individual, interconnected machines that achieve a common goal. Their popularity and use have gone up in recent times due to their ability to provide horizontal scalability on the server-side, where the ‘power’ (which can mean processing power or storage power) of the system can be scaled up by introducing more machines, rather than increasing the ‘power’ of an individual machine (known as vertical scaling).

The main challenges that come with designing such systems are due to two factors:

- Lack of a global clock: Conventional systems and algorithms that operate on local hardware are synchronized since their commands are run at the pace of the global clock in the CPU. With distributed systems, there is no such synchronization. Certain components can take an indefinite amount of time to execute their part of the program and the system needs to be tolerant of that.

- Component failures: Whenever a number of machines are present in a single system, there is always the probability of independent failure of individual machines. This causes problems in the consistency and availability of the system. Distributed systems need to be designed and implemented to be tolerant of such failures.

- Unbounded Latency: In asynchronous, real-world networks, the time that a message takes to travel from one system to another is unpredictable and has no fixed upper bound, i.e., there is no way to ensure that every message always reaches its destination within a fixed interval of time.

Such challenges make solving even the simplest problems using distributed systems, extremely tricky.

DNS

In the current TCP/IP model of the internet, the address to all web resources are defined by their numeric IP address (eg. 172.217.174.238). However, these IP addresses are hard to remember.

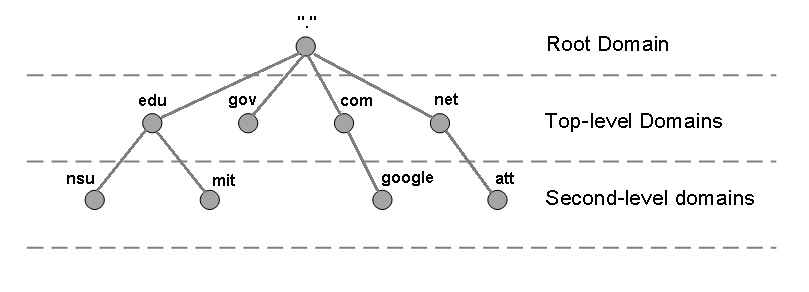

Domain Name Server (DNS) is a standard protocol that helps Internet users discover websites using human-readable addresses (eg. github.com). Like a phonebook that lets you look up the name of a person and discover their number, DNS lets you type the address of a website and automatically discover the Internet Protocol (IP) address for that website. Under the hood, it is often constructed as a hierarchy of nameservers that progressively resolve a given domain name into the corresponding Internet address.

Image Credits: https://www.itgeared.com/articles/1354-domain-name-system-dns-tutorial-overview/

Image Credits: https://www.itgeared.com/articles/1354-domain-name-system-dns-tutorial-overview/This also offers another advantage: It makes the web resource IP address agnostic, meaning that the resource will not be tied to the IP address of the node it is on. This means that the IP address of the node can be changed and the resource can still be accessed through the same human-readable name. In this way, it provides a kind of abstraction between the web resource and the user since they don’t need to deal with the complexity associated with using IP addresses to access web resources.

Without DNS, the Internet would collapse, since it would be impossible for people and machines to access servers via the friendly URLs they have come to know. The domain name system uses a tree-like hierarchy of name servers to process queries.

This project describes a strongly consistent approach to implementing a DNS service that involves the Raft Consensus algorithm. The project also explores the deployment of this distributed DNS service on AWS, making the service geographically distributed.

Raft Implementation and Replicated Key-Value Store

Our implementation of this project can be found in the main branch of this repository. It includes an implementation of the Raft Consensus algorithm and a replicated key-value store. The key-value store uses Raft for consistency of data among its replicas and for fault tolerance.

Articles related to the explanation of Raft and our implementation can be found in the repo’s Wiki.

Why Raft and Motivation for a Raft-based DNS?

Conventionally, the Paxos consensus algorithm has been the default choice for implementing consensus in a distributed system. While it is quite functional, it has always been complicated to understand and notoriously tricky to implement. These issues with Paxos have been elaborated on, in the Raft consensus paper. In fact, the paper itself is named ‘In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm’, highlighting the opaqueness of Paxos. Hence, we have implemented our DNS service based on the Raft Consensus algorithm.

The consensus problem essentially explores ways of making multiple entities agree on a specific value. This can be extended in the case of Raft since it allows for the multiple entities to maintain a common log of values.

Raft is designed to achieve this kind of an agreement based on three aspects:

- Leader Election: The algorithm works on the basis of electing a participating node as a dominant entity. This ensures that there is always a node that decides the value that the system must agree upon. In this way, the problem of making entities agree upon a value is reduced to electing an existing node as a leader.

- Log Replication: Since the leader of the system is the dominant entity, the other nodes, or the followers, would need to synchronize their log entries with that of the leader. In a way, the leader is the entity receiving the log entries from the clients and replicating the entries on all the other follower nodes.

- Safety: This property would refer to the fact that for any committed log entry in a given node, there shouldn’t exist a different log entry on the same position in another node that has been committed. This would ensure that the same log entries have been committed in each replica, and that no committed entry ever has to be rolled back.

The leader election procedure can be described in the following steps:

- All nodes in the system start as a follower, with an election timer (the duration of the timeout is semi-randomized so that all nodes don’t timeout at the same time. For instance, the Raft paper suggests that the duration of the timeouts should be a random value between 150-300 milliseconds).

- Once the timer runs out for a particular node, it becomes a candidate, and sends requests for votes to every other node.

- Nodes then accept or reject the candidate as the leader and send their decision to the candidate. If a majority of nodes accept the request, the candidate becomes the leader.

- The leader then continues to accept log entries from the client and replicates them on the various nodes, thereby adding them as commits.

To prevent further elections by the election timer of a node timing out, the leader periodically sends heartbeat messages to all the nodes, which resets their election timers.

In this way, we can observe how, even when the leader crashes or disconnects, another leader can be elected and the system can still be made to be available. The only situation where this system can fail is when the majority of the nodes have crashed or are unavailable.

The mechanisms used by Raft can be read about in greater detail in the Raft paper and our repo’s Wiki.

So clients interacting with the system would always have to make requests to the current leader of the system.

Thus, Raft, being a (relatively) simple to understand and convenient to implement algorithm, formed the basis for this project.

Motivations for a Raft-based DNS: In the paper Measuring Update Performance and Consistency Anomalies in Managed DNS Services, the authors benchmark multiple major managed DNS services (NS1, Cloudflare, Dyn, etc.) and point out that “The intense focus on optimizing lookup performance coupled with DNS’ inherent expectations of weak consistency has had unfortunate side effects: updates are inexplicably slow and MDNS providers pay scant attention to consistency correctness. […]. Furthermore, we find that 6 of the 8 MDNS providers violate monotonic read consistency under frequent updates and at least one large MDNS provider appears to violate even eventual consistency.”. Constructing a Raft-based DNS service with stronger consistency guarantees can solve some of the issues mentioned.

Extending the Implementation to a Geographically Distributed DNS

Our simple DNS service stores only two types of records - NS records and A records. Basically the key-value store is used here, with the key being the “name” of the record (eg. github.com) and the value containing its type and the associated value (eg. A,13.234.210.38).

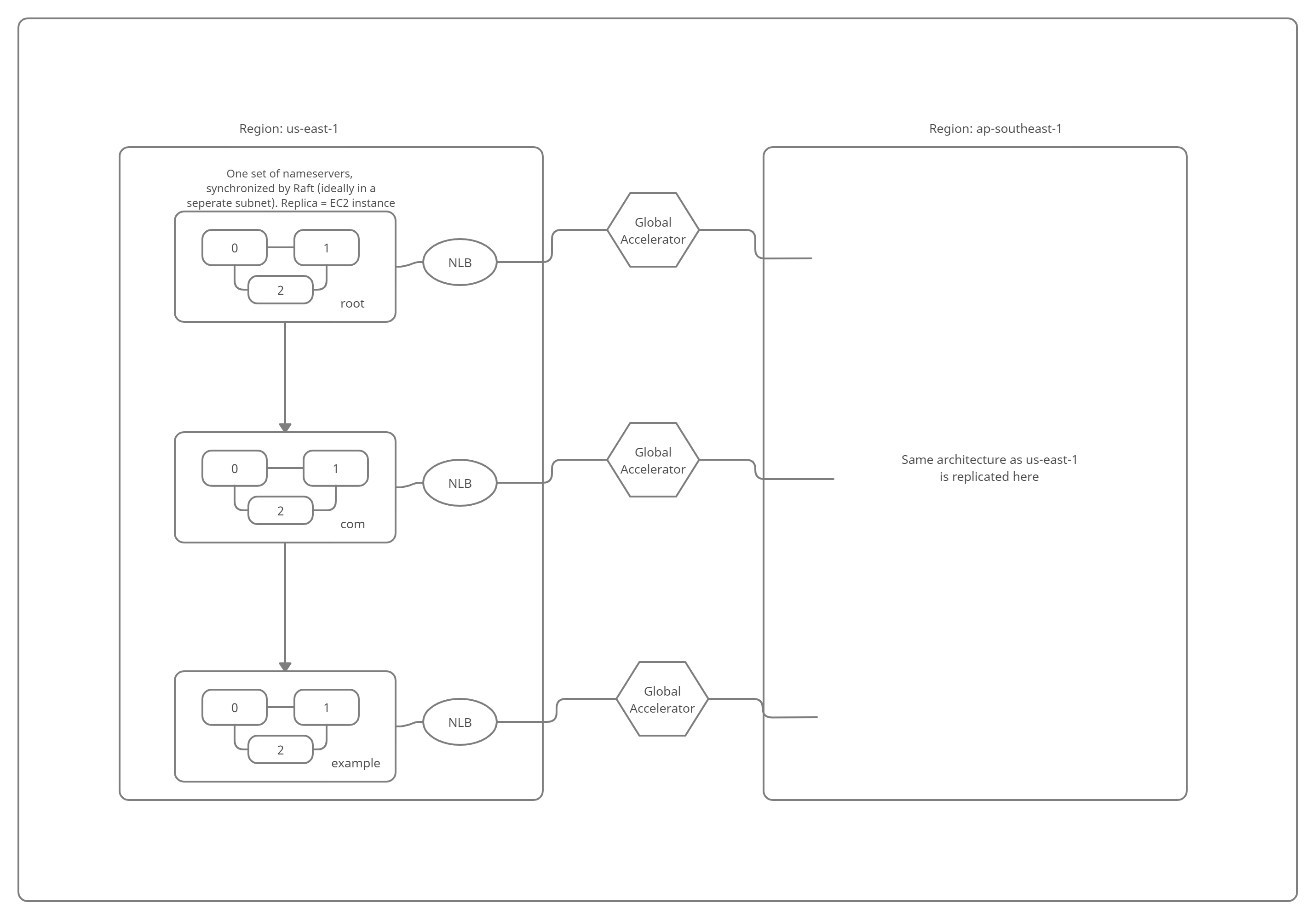

Using AWS services, we will setup a hierarchy consisting of a set of replicas responsible for being the root nameservers, a set of replicas being responsible for a single TLD (like “com” or “org”, etc.) and a set of replicas being responsible for the “example.com” domain. Let’s call each set of nameserver replicas a “nameserver group”. For each region that we want our DNS to be present in, the same structure of nameserver groups is replicated. Geographically distributing it provides an additional level of redundancy and ensures that the time taken to serve requests for a client anywhere in the world remains relatively low.

A rough AWS architecture diagram is as follows:

Each larger rectangle enclosing 3 instances represents a nameserver group. As can be seen, we have 3 nameserver groups in each AWS region, (we have chosen 2 regions here, us-east-1 and ap-southeast-1) and each nameserver group is an independent set of raft replicas. (Each nameserver group consists of 3 replicas). Each replica of a nameserver group is an EC2 instance and normally contains data that is identical to the other two replicas.

Whenever a DNS record needs to be written, the request needs to be sent to the leader replica of the corresponding nameserver group of every chosen AWS region (e.g. if we wanted to write a record to the root nameservers, we will have to send a request to the leader of the replicas responsible for being the root nameservers to both regions). However, the address of the leader of each nameserver group is subject to change and will not remain constant. This is because when the initially elected leader crashes or is disconnected from the other replicas due to some kind of network partition, a new leader will be elected. In addition, each EC2 instance has a different public IP address, which changes whenever an instance is stopped and started.

To have one single address that points to the leader replica which the client can use to make requests to a given nameserver group, we create an AWS Network Load balancer (NLB in the figure above) for each nameserver group. Whenever a new leader is elected among the replicas, the new leader informs the corresponding load balancer to send all client requests to itself. Each NLB has a fixed address.

Since nameservers are spread across the globe (for demonstration purposes above we’ve used only 2 regions), we would want to route requests made by clients to the closest region (based on latency). For this, we can use AWS Global Accelerator (Global Accelerator in the figure above) that uses IP Anycasting to provide a single IP address that will point to the load balancer address which is closest to the client. We use the Global Accelerator provided anycast IP for read requests. Write requests are performed directly using the NLB addresses, since the write needs to be performed on the corresponding nameserver group in every region.

Note: Normally, different organizations would be responsible for setting up nameservers for the domain it’s authoritative for. We are demonstrating an alternate way that organizations can use to set up nameservers.

Simulating the Setup

The code for this section can be found in the aws-dns branch of the repo.

We setup the architecture as follows:

We use AWS EC2 Launch Templates to launch multiple EC2 instances at the same time. We provide scripts that each instance will run at startup using the User Data feature. For the example architecture above, we will launch 9 instances at once in each region (total 18 instances) using the launch template. The user data we provide each instance tells it to do the required setup work (install the Go compiler, clone the repo containing the source code, build the source code, etc). Then, each instance will want to get itself assigned as a replica of a nameserver group. For this, it contacts an “Oracle” (another script talked about below) that is running somewhere that is accessible over the internet, and asks the oracle to register itself (by providing data such as it’s EC2 Instance ID and the region it belongs to).

Once the remaining replicas in that nameserver group also register themselves with the oracle, the oracle will inform each replica in that nameserver group about the addresses of the other replicas (required for inter-replica communications for maintaining consistency), the address of the load balancer assigned to the nameserver group it belongs to (specifically, the ARN (Amazon Resource Name) of the NLB) and the EC2 Instance IDs of the other replicas. Each replica then stores this data as environment variables.

Once this is done, the replicas in the nameserver group elect a leader replica using the implemented leader selection algorithm, and this replica informs the associated NLB (using the NLB ARN obtained from the Oracle) to deregister other registered target(s) (if any), and register itself. This will result in all requests made to the Load Balancer being routed only to the leader.

The Oracle

The Oracle is a key piece of the setup. It is implemented as a Python program (https://github.com/krithikvaidya/distributed-dns/blob/aws-dns/AWS/oracle.py) using a simple Flash webserver to listen for HTTP requests. We run it on a separate EC2 instance and access the server from the outside using the instance’s public IP. On starting up the Oracle, we need to make a request to the /init endpoint specifying the following parameters:

n_regions: the number of AWS regions we want to run our setup in,region_names: the names of the above AWS regions,instances_per_region: the total number of EC2 instances set up per region (will be 9 in the figure above),replicas_per_ns: number of replicas per nameserver group (should be divisible byinstances_per_regionand ideally an odd number).

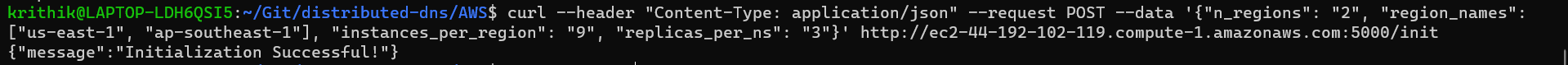

The request we can make considering the architecture provided in the previously mentioned figure will be:

curl --header "Content-Type: application/json" --request POST --data '{"n_regions": "2", "region_names": ["us-east-1", "ap-southeast-1"], "instances_per_region": "9", "replicas_per_ns": "3"}' http://<public ip of ec2 instance running the oracle>:5000/init

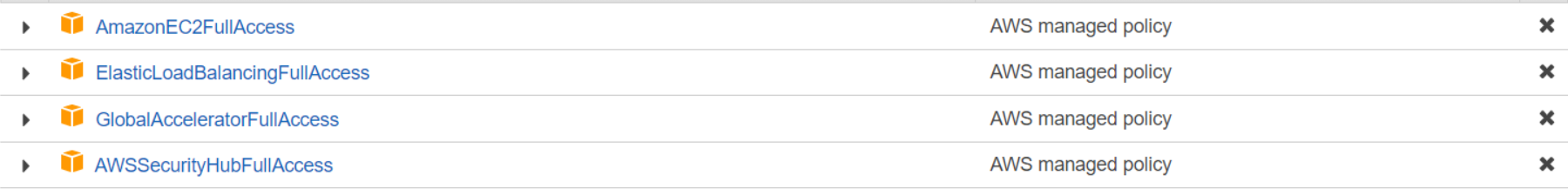

Once this is done, the oracle makes requests to AWS to create the NLBs (total 6 NLBs in our setup, 3 in each region), the associated listeners and target groups for each NLB. To access/modify AWS instances associated with our account, we need to provide the instance it runs on with an IAM role, talked about in the next section. Once all the load balancers are provisioned and have their status as “active”, it makes requests to AWS to create the Global Accelerators (3 in total), and associates each Global Accelerator with the appropriate NLBs. After this, the initialization process is complete.

Replicas can then register themselves with the oracle using the /register_replica endpoint. Once sufficient replicas have registered in a region to form a nameserver group (3 in our case), it will assign those replicas to be part of a nameserver group and respond to each such replica with the details of the other replicas, as mentioned above. When the next 3 replicas register in that region, another nameserver group is formed and so on (total 3 nameserver groups in each region).

The Oracle does not directly send the details of other replicas once a nameserver group is complete, it sends them when the replica makes a request to the /get_env endpoint.

How to run the setup

-

Clone the

aws-dnsbranch of the repogit clone https://github.com/krithikvaidya/distributed-dns.git -b aws-dns --single-branch cd distributed-dns -

In your AWS management console, you will first need to create two IAM roles, one to provide the Oracle with permissions to interact with and provision resources in the cloud and the other to allow the replicas to interact with and modify attributes related to their associated NLB.

In the IAM console, create a new role for EC2 instances with the following policies attached (call this IAM1):

Similarly, create another role for EC2 instances with only the ElasticLoadBalancingFullAccess policy attached (call this IAM2).

-

You will need to run the Oracle such that the webserver it defines is accessible over the internet. For this you can create an EC2 instance with the IAM role that was created previously (IAM1) attached to it, a security group allowing inbound SSH traffic and inbound TCP traffic at post 5000 (which is the port at which the server will be listening), and user data as specified here. Launch the instance and let the instance state change to “Running”. Note down it’s public IP address.

-

Wait for sometime so that the user data script on the oracle completes executing and the Flask server is started. This can be verified by checking the EC2 startup logs by ssh’ing into the instance and running

cat /var/log/cloud-init-output.log. Then, make a POST request from your device to the/initendpoint, specifying all the parameters of your setup, an example being as follows (same example as above):curl --header "Content-Type: application/json" --request POST --data '{"n_regions": "2", "region_names": ["us-east-1", "ap-southeast-1"], "instances_per_region": "9", "replicas_per_ns": "3"}' http://<oracle_public_ip>:5000/initAfter the oracle completes the initialization procedure, it will respond with the message “Initialization Successful”:

-

In each AWS region that you will be running nameservers in, create a launch template for EC2 instances. The launch template should specify Ubuntu as the OS (tested with Ubuntu 20.04), specify a security group that allows inbound traffic for port 4000 from anywhere and inbound SSH access (port 22) from anywhere, the previously created IAM role (IAM2) attached, and should define the user data as specified here. NOTE: the value for the

ORACLE_ADDRin the last line of the user data should be edited to match the public IP address of the Oracle. -

Then, you can launch instances in each region using the template (the number of instances will be equal to the

instances_per_regionyou defined in the init request to the oracle. In our case, it will be 9). Ensure that the availability zone chosen is the “a” AZ (eg: us-east-1a), since the script configures the load balancers to only route requests to replicas in the “a” AZ. -

Wait for a few minutes so that all the instances can get set up, run the user data scripts, start the Raft server, register itself with the oracle and initialize its environment variables from the oracle. After this is done, each set of replicas responsible for a nameserver will choose a leader to receive requests, and the leader will tell the corresponding load balancer to direct all the traffic to itself. This takes a few minutes.

-

You can now interact with the DNS service (examples shown below).

NOTE: the oracle script does not automatically delete/deprovision resources when terminated. You will manually need to delete the created global accelerators and for each region, delete the load balancers, delete the target groups and terminate the launched EC2 instances after usage is done.

Sample Interaction

For interacting with the DNS service, two scripts have been written (write_record.go and resolver.go). An example usage of theirs is shown as follows:

Say we are trying to store the address for wikipedia.org and it’s IPv4 address is 103.102.166.224

-

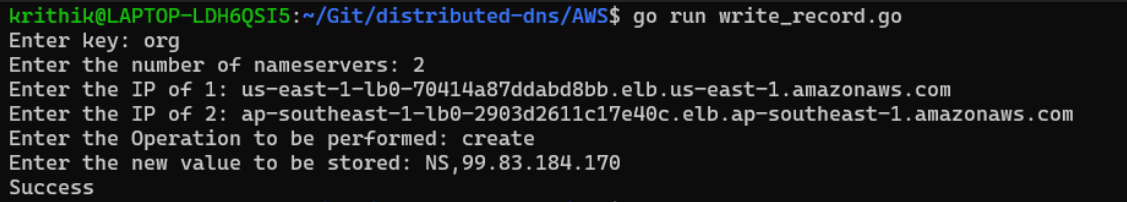

First we will write the address of the nameserver responsible for the “org” domain in the root nameservers as an NS record. We run the write_record script as follows:

The two addresses entered above are the addresses of the load balancer in the us-east-1 and the ap-southeast-1 regions responsible for routing requests to the leader of the root nameservers (these addresses can be found through the “Load Balancers” section of the EC2 Management Console). AWS doesn’t directly expose the IP address of the load balancers, only tells us its DNS name (which is somewhat redundant), but we can assign a static IP to each load balancer using the Elastic IP functionality.

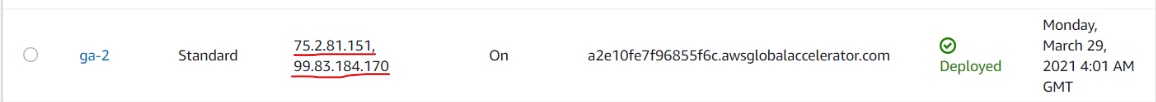

The IP address stored in the value of the record is the Global Accelerator address that points to the load balancers responsible for the nameservers responsible for the “org” domain in each region.

Either one of these IPs could be used

Either one of these IPs could be usedNOTE: Real world DNS “NS” records never store IP addresses, they store the DNS name of the authoritative nameserver that’s next in the hierarchy. If the address of the nameserver is a subdomain under the domain it’s authoritative for (e.g. ns1.google.com is an authoritative nameserver for google.com), then the IP address of such servers are stored in the ADDITIONAL section of the DNS response to prevent infinitely looping resolutions (also known as “Glue Records”). For simplicity, we directly store the IP address of the next nameserver in the NS record.

-

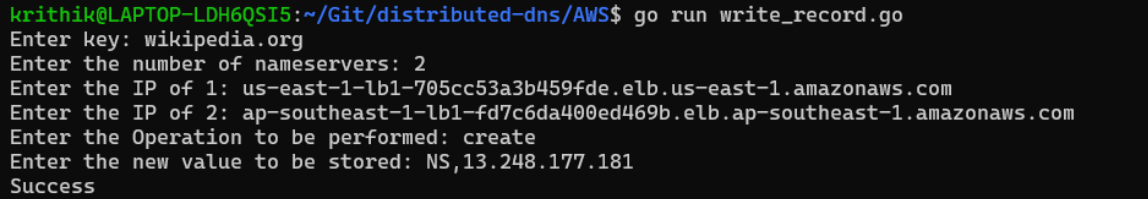

Then we will write the address of the nameserver responsible for the “wikipedia.org” domain in the nameservers responsible for “org”, as an NS record. We run the write_record script as follows:

-

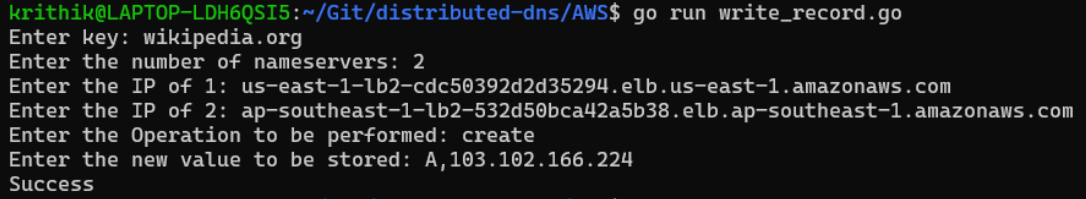

The nameservers responsible for the “wikipedia.org” domain are the authoritative nameservers for wikipedia.org. We will write the desired A record (IP address) of wikipedia.org here.

The process of writing the record is now done. In the future, if someone wished to write the A record for another .org domain, they would only need to perform step 3 above with the required A record.

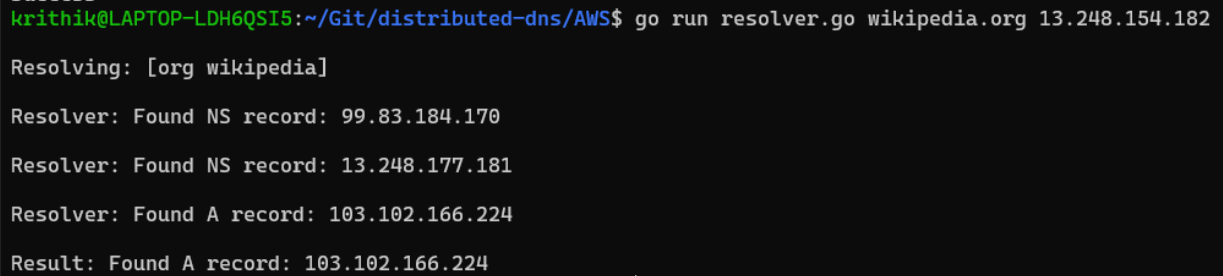

Resolving a record

We supply the name we wish to resolve and the address of the root nameserver (Global Accelerator address) as input to the resolver script. The resolver recursively performs the resolution process until an A record for the given name is obtained.

Conclusion

This project involved implementing a replicated key-value store using Raft consensus for consistency, and then building upon it to set up a sample DNS service on the cloud with better consistency guarantees than what most real-world managed DNS services provide. The project has scope for improvement, with some low hanging fruit related to optimizations. These are:

- Raft requires all requests (reads and writes) to go through the leader to maintain linearizable consistency. When a client sends a read request, the leader sends a heartbeat to the other replicas (the followers) to ensure that it is still a leader, before responding to the request. This can be quite slow, and we can use a modified version of Raft using leader leases to improve read performance (since the vast majority of the requests to a DNS service would be read requests, this would be a good optimization).

- If we are willing to give up linearizable consistency and only work with strong eventual consistency (i.e. once a write is performed, some replicas may not return the latest written value during a read, but eventually the write is reflected in all replicas), we can allow reads to be served from any replica (not just leaders).