Disclaimer: This article is not an introduction to blockchain, it does try to cover some basics of blockchain, but it’s focus is more on the proof-of-work as an approach to solving consensus problem.

Terminologies and breakdown

The title of the article contains “consensus mechanisms in blockchain”, which sounds like a title with heavy words. So let’s try to first breakdown this title and understand each term separately.

- Consensus : “Consensus” in simple terms means reaching an agreement amongst a set of parties about a specific thing like an event or a data value. Consensus is collaborative and cooperative in nature by the parties seeking agreement. So one word mapping, consensus = global agreement

- A Consensus mechanism is an algorithm or approach through which a multi-party system can reach consensus/agreement.

- Blockchain : Now coming to the system under discussion today which is blockchain. Blockchain has really been in a huge buzz for a long time and mostly because of its application in the implementation of the bitcoin network which as its creators call it “A peer to peer electronic cash network”. Blockchain as a piece of tech is being studied standalone now in a neutral manner to leverage its strengths that have been used in the bitcoin network. In simple terms blockchain is kind of chain of blocks or a ledger(of blocks) that can keep a record of transactions of any sort, whether it is financial transactions( bitcoin network being the example) or transactions about ownership of assets, documents or even storing the state of computer code(used in “programmable” blockchains like ethereum). This ledger allows us to keep a history of all the transactions that were carried out. In simple terms a blockchain = A ledger/chain of blocks that represent a set of transactions/events and thus record a history of all transactions.

Distributed nature of blockchain

Now let’s take a step back, if this ledger were just any ledger that a person/computer system can keep a “local” copy of, then it is not very interesting, the real use of this ledger comes when it becomes “distributed” in nature, i.e, all the parties involved in recording the history of transactions/events participate in maintaining a shared global copy of the ledger that they all should agree to. Again when we say a global copy, there is no one copy uploaded on a centralized server to which each person reads and writes, but rather each party in the network holds one local copy that they try to keep in sync with the rest of the network and if majority of people have the same copy of ledger then we consider that most people are in “consensus” with the history of transactions/events or in other words most people have a common “global view” of the ledger. Maybe for now this seems a simple task, let’s explore the workings of such a distributed ledger system and what sort of problems it can encounter trying to reach the consensus about the state of ledger.

Byzantine’s Generals and Consensus problem

Let’s first setup a very simplified version of a problem called “Byzantine’s Generals Problem”. This is a classic problem modeled in computer networks and distributed systems. The problem is as follows:

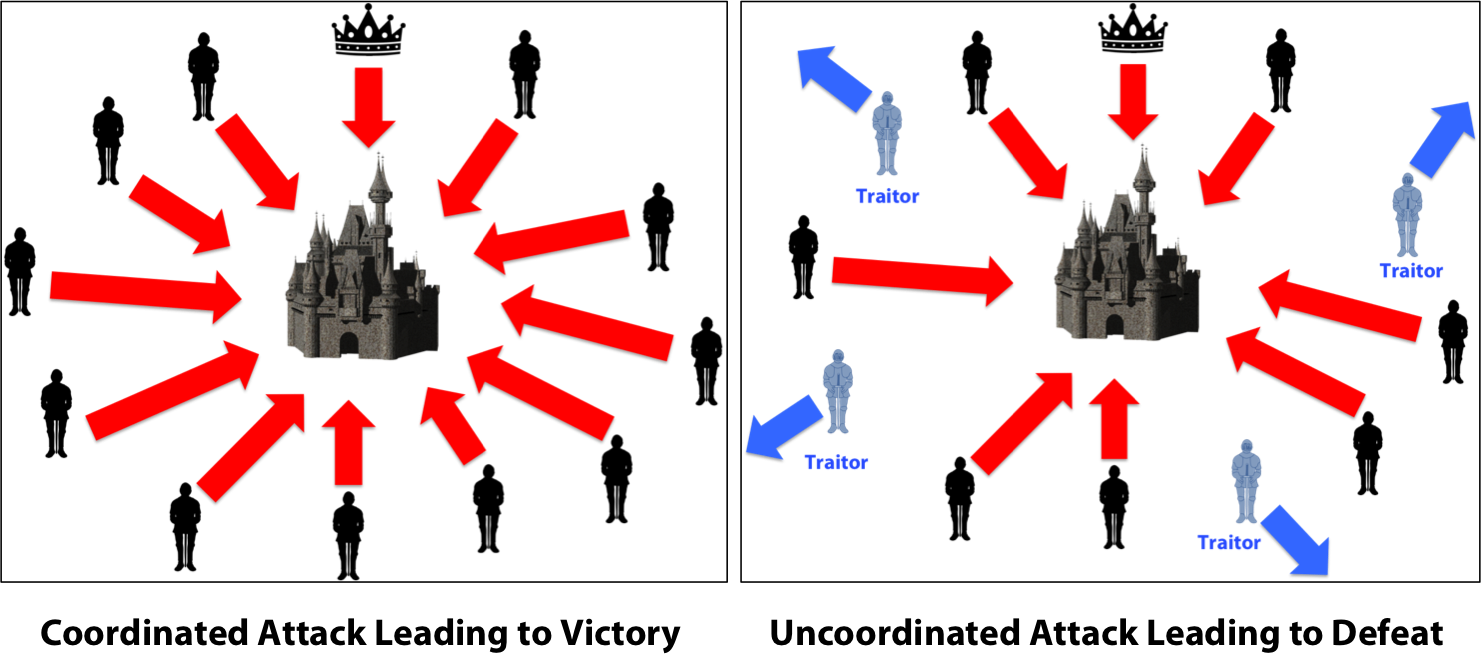

- There is a group of generals each commanding a portion of Byzantine’s army, encircling a city they are planning to attack. In simplest form the generals must decide upon either to “attack” or “retreat”.

- The generals are separated by sizeable distance and hence can communicate only via some messengers.

- Some of the generals have to send message to other generals about their view on “attack” or “retreat” and then all of them in the end have to agree somehow to either attack or retreat.

- The attack can succeed only if a majority of generals attack at the same time. Else it has high chances of failure. Hence it is crucial to attain agreement on the issue.

- This sets up a series of problem. This situation has an issue of trust and consensus. First problem,whatever information the messenger has given is it untampered or not. Second, also after receiving the information, whatever decision a general has made is it in agreement with all other or at least a majority of generals or not. How to know what is the global view of all the generals about attacking the city. The problem can be made complicated by having traitors in the system.

The above problem can be modelled in the context of blockchain:

- The generals map to the nodes in the blockchain’s network

- The messengers map to the network of communication

- The problem of agreeing to an attack strategy maps to the problem of having a consensus on the global state of transactions of the network.

This problem can be solved in blockchain through various consensus mechanism of which we will focus on something called “proof-of-work”. This consensus mechanism was first outlined in a paper by Satoshi Nakamoto(who is still not known) and in a list of emails in his conversations with his peers. We will first look at what is involved in proof-of-work and then how it solves the consensus problem.

Proof-of-work: The consensus machine behind blockchain

- This is the meat of the article, so buckle up.

- In a blockchain network, any transaction/event is broadcasted to all the nodes of the network.

- The nodes take up these transactions. They form a block of data containing the transaction details, the hash of the previous block(parent) and have to add something called “nonce” and generate a hash value.

- The difficult part is the hash value to be generated has to follow a certain pattern. In case of bitcoin blockchain, the hash should have specific number of leading zeroes in the value. More the number of leading zeroes more intensive the task is and less the zeroes less intensive it is. Thus they can adjust nonce value to find this hash.

- The way to look for the right nonce is simply brute force which is a very computationally intensive task

- A set of nodes that received the transaction start “mining” a block whose hash value will be accepted by the blockchain.

- More the compute power higher is the chance of getting the work done. Hence if nodes form a pool and a majority of nodes start working on a block, they will get the required hash first. This shows that majority of people (sort of) stand behind that particular transaction and “agree” on it. Here we start seeing the beginnings of reaching agreement/consensus on the event that has occured.

- But if multiple transcations take place at same time, any node can receive any transaction. The key here is whichever transcation is received by “majority” of nodes has a higher chance of forming a valid block first and is being agreed upon by a majority of nodes.

- Thus in blockchain network, the nodes show their vote/agreement via the compute power. The more the compute power behind an event/transcation, more nodes agree on it.

- But the next question is how is the local copy of the ledger that is formed by nodes update to be in sync with what the other nodes have.

- Whenever a block is successfully mined, it is broadcasted to the network. The nodes who are honest have to accept this mined node after verifiying it and add it to their local copy. Thus this synchronizes the local ledger copies. Also if multiple blocks are broadcasted then the blocks that form a “larger chain” are to be accepted. This is also called the longest chain rule. The larger chain bascially shows that it has more compute power backing its formation, thus majority agreeing to it.

- Now if we consider a set faulty nodes who are trying to introduce false blocks, then they need more compute power than rest of the network to form a longer chain by racing against the network. If majority of nodes are honest this is not possible.

- Also if a faulty node tries to change the transcations before, they have to “re-mine” the blocks ahead since they are cryptographically linked by the hashes of previous blocks and the cost of re-mining is very large, it is next to impossible to change the order of events or even the events itself.

- Thus blockchain network works by reaching a consensus on the set of events/transactions and the order of those events as well by the nodes casting their votes in terms of compute power. Here the nodes need not trust each other to agree, but just follow the rules of work and they can automatically reach a consensus.

Conclusion and Ending remarks

Thus proof of work is a consensus mechanism where the nodes vote to back a transaction/record in the ledger by providing their compute power as a vote. The more the votes or “compute power” behind a particular copy of blockchain/ledger, means more parties “agree” on that particular ledger and history of transactions. Thus all the parties can always agree and trust the other nodes by possessing the longest proof-of-work chain and can know for sure that their copy is in sync with the common global view of the ledger.

The proof-of-work chain is how different synchronization, distributed database and global view problems can be solved.

Blockchains can have other consensus mechanisms as well, like Proof-of-stake, Federated-Byzantine-Fault-Tolerance, Proof-of-activity and so on. But proof-of-work is the earliest of the mechanisms trying to solve the Byzantine Agreement and develop a Byzantine fault tolerant system. It certainly has drawbacks but is one of the most robust mechanisms and many mechanisms still draw the concepts from proof-of-work.

Proof of work outlined by Satoshi Nakamoto

The proof-of-work chain is a solution to the Byzantine Generals’ Problem. I’ll try to rephrase it in that context.

A number of Byzantine Generals each have a computer and want to attack the King’s wi-fi by brute forcing the password, which they’ve learned is a certain number of characters in length. Once they stimulate the network to generate a packet, they must crack the password within a limited time to break in and erase the logs, otherwise they will be discovered and get in trouble. They only have enough CPU power to crack it fast enough if a majority of them attack at the same time.

They don’t particularly care when the attack will be, just that they all agree. It has been decided that anyone who feels like it will announce a time, and whatever time is heard first will be the official attack time. The problem is that the network is not instantaneous, and if two generals announce different attack times at close to the same time, some may hear one first and others hear the other first.

They use a proof-of-work chain to solve the problem. Once each general receives whatever attack time he hears first, he sets his computer to solve an extremely difficult proof-of-work problem that includes the attack time in its hash. The proof-of-work is so difficult, it’s expected to take 10 minutes of them all working at once before one of them finds a solution. Once one of the generals finds a proof-of-work, he broadcasts it to the network, and everyone changes their current proof-of-work computation to include that proof-of-work in the hash they’re working on. If anyone was working on a different attack time, they switch to this one, because its proof-of-work chain is now longer.

After two hours, one attack time should be hashed by a chain of 12 proofs-of-work. Every general, just by verifying the difficulty of the proof-of-work chain, can estimate how much parallel CPU power per hour was expended on it and see that it must have required the majority of the computers to produce that much proof-of-work in the allotted time. They had to all have seen it because the proof-of-work is proof that they worked on it. If the CPU power exhibited by the proof-of-work chain is sufficient to crack the password, they can safely attack at the agreed time.

The proof-of-work chain is how all the synchronisation, distributed database

Interesting links and Furthur Reading

Here is the link to the mails that very exchanged between “satoshi nakamoto” and his peers discussing the idea of “bitcoin and blockchain”:

Here is the link to the original paper published: