Self-Flying Planes

Abstract

I find it fascinating how, as they gain a better understanding of the level of autonomy in current planes, people become more comfortable with concepts like self-flying planes. Modern planes are self-flying in the sense that they can execute a flight plan devised by pilots on their own. These planes, on the other hand, can’t think for themselves; they’ll stick to the flight plan unless it’s changed. When pilots remove the seatbelt indicator, for example, you’re probably on a self-flying plane. With this information, and the increasing number of successful flights every day, autonomous aircraft appears to be a safe and feasible breakthrough. When a commercial aircraft is still on the ground, the flight plan is entered into the flight management system (FMS). The autopilot is normally turned on a few minutes after takeoff by the pilots. Until a few minutes before landing, the autopilot is usually turned on. This isn’t always the case, though. If the plane and runway are certified for autonomous landings in low visibility, the plane can direct itself to a safe, smooth touchdown. Pilots are on hand to deal with changes and potentially dangerous conditions such as diversions, turbulence, and emergency situations. They’re a safety feature in the cockpit that keeps an eye on what’s going on with the plane. For example, it is the pilots’ responsibility to keep the autopilot on track; if it fails, they must assume control.

The Difference Between Autonomous Aircraft and Self-Flying Planes

Although self-flying planes are highly automated, they still require two competent, well-trained pilots.

Modern autopilot systems are built to respond to commands from the pilot or the flight director computer. At cruising altitudes, the autopilot keeps the plane on a predetermined path. It can even follow instructions for climbs, descents, and curves. You can imagine the autopilot following an airway, which is an unseen highway.

Planes are unlikely to encounter birds or other obstructions at cruising altitudes. As a result, the autopilot does not require freedom of movement.

Aircraft will no longer be partially automated; instead, they will be entirely autonomous, obviating the necessity for a pilot.

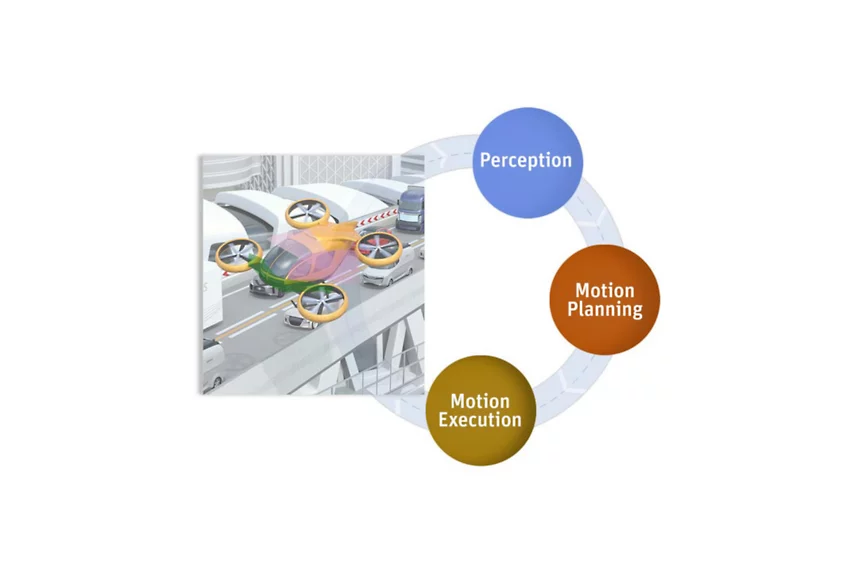

Urban air mobility is one of the most common uses for autonomous aircraft. These self-driving flying taxis, as they’re known in the industry, can transform personal transport and shipping in megacities by lowering traffic and improving safety. Designing these autonomous planes to operate in such a crowded environment, on the other hand, presents engineering challenges far more difficult than those overcome by the advent of existing autopilot systems.

Aside from flying a predetermined route, autonomous aircraft will need to safely fulfil three very crucial roles in order to operate in an urban environment:

- Landing and taking off without a runway

- Identifying potential roadblocks (like vehicles, buildings and birds)

- Changing course to deal with unforeseen circumstances (like wind gusts, engine failures and obstacles)

Sensors, embedded software, and artificial intelligence (AI) systems that continuously detect unsafe conditions, determine a safe path of motion, and execute those actions are required for this level of autonomy. In any area or weather situation, these systems will need to be able to distinguish between buildings, birds, and other aircraft. Such a system necessitates extensive engineering development, including simulation, software, and hardware-in-the-loop testing.

What Will the Future of Aviation and Autonomous Aircraft Look Like?

Moving to single pilot operations will be the first step toward autonomous aircraft in the future.

There have already been whispers of launching single-pilot operations for freight and short-haul aircraft.

Flights for urban air mobility will also require a single pilot or complete autonomy.

Fully autonomous systems will be more qualified than humans to tackle city skies crowded with impediments due to their speed and reliability.

These compact, light urban vehicles will also be capable of vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL). As a result, they may be able to transport four people. Short-distance flights between municipal airports could carry up to 14 passengers. As a result, businesses cannot allocate space or weight to two pilots and expect to break even financially.

Aside from autonomous features, urban aircraft will differ significantly from existing aircraft, necessitating:

- Electric propulsion to reduce pollution in cities

- Lightweight frames/loads for maximum manoeuvrability and efficiency

- Quiet systems to minimise urban noise to a minimum

- Comfortable experiences to enter into the urban mobility market

Many major and startup firms are currently competing to supply these self-driving vehicles in cities.

How to Get from Self-Flying Planes to Autonomous Aircraft

To make autonomous aircraft a reality, a lot of work will have to be done on sensors. In an urban area, you can’t just place a camera on an aircraft and expect it to see everything. Cameras, like the human eye, would be rendered ineffective in certain situations such as fog and glare.

To comprehend the environment, engineers will need to build radar, lidar, cameras, sound, and infrared sensors. They’ll next need to use sensor fusion approaches to combine the data from various devices to get an accurate picture of the environment for each flight and weather situation.

The perceived data must then be sent to the aircraft’s internal software and AI systems so that a safe flight may be planned. To ensure functional safety, these systems will need to be created and tested. To put it another way, engineers must ensure that the autonomous aircraft makes the safest decision possible in every circumstance. These testing may take decades, if not longer, without simulation.