Introduction

Let me preface this article with something: There’s a very good chance that your password is not secure. In fact, if it’s anything less than nine characters long, any attacker could crack it in seconds if he had a decent GPU. Most of us know that ‘password’ is a very weak choice for a password, but there are some of us who think we’re smart and keep our passwords something like ‘p@$$w0r6’: It’s a terrible idea. Change it right now. ‘Hello123’ is probably safer than that. So what exactly is a safe password? And how do you even store passwords securely? Let’s try to answer these questions. Also, let’s do some password cracking along the way to see if what we come up with is actually secure.

Storing Passwords Securely

Usually the data on a server is protected only by the web security measures in place. When these fail, the server is compromised and the data is available to the attacker. For sensitive data like passwords, this becomes a huge problem. Password security provides an added layer of security. It ensures that no kind of usable data can be extracted from the password data stored on the server. Let’s discuss certain techniques for storing passwords:

1. Plaintext:

This is the naive approach to storing passwords. So for example, if a password is something like ‘p@ssword1234’, it would be stored as is in the web server. It makes logical sense: The username and password are stored along with each other on the server and when the user wants to authenticate, the backend code checks the data they gave as input with the data on the server. But obviously, this is a terrible idea. Any attacker who gains access to the server, basically has access to all the passwords.

2. Encryption:

Let us go one step further and encrypt all the passwords with a symmetric key (keys which can both encrypt and decrypt data) before storing them. When a user needs to authenticate, the password in the server is decrypted using the key and checked with the entered password. This is a little better since an attacker cannot just read all the passwords by gaining access to the server. But if he finds the encryption key somehow, the passwords can be decrypted easily. So to eliminate this problem, we need a kind of encryption which cannot be reversed. This is where hashing comes in.

3. Hashing:

In simple words, a hash function generates a unique, fixed length string signature for an input data of any arbitrary length. The keywords to note here are unique and fixed length. Unique means that there exists only one hash for a specific input data. Fixed length implies that significant data loss has occurred during hashing, which means that the original data cannot be obtained from the hash string.

We can use these properties of a hash to our advantage while storing passwords. So, instead of storing the passwords themselves, we store their hashes. During authentication, we hash the password input from the user and compare it with the hash stored in the database. Since hashes are unique to a string, comparing them is equivalent to comparing the original strings. Thus we can perform authentication without really knowing the actual password of the user.

This sounds good. The attacker has no way of obtaining the original password from the hash. So it should be secure right? Wrong. Instead of just explaining why, I’ll demonstrate how to crack hashes.

Password Cracking

For this exercise, we will be using hashcat. Hashcat is an open source password recovery tool which uses GPU hardware acceleration to crack passwords.

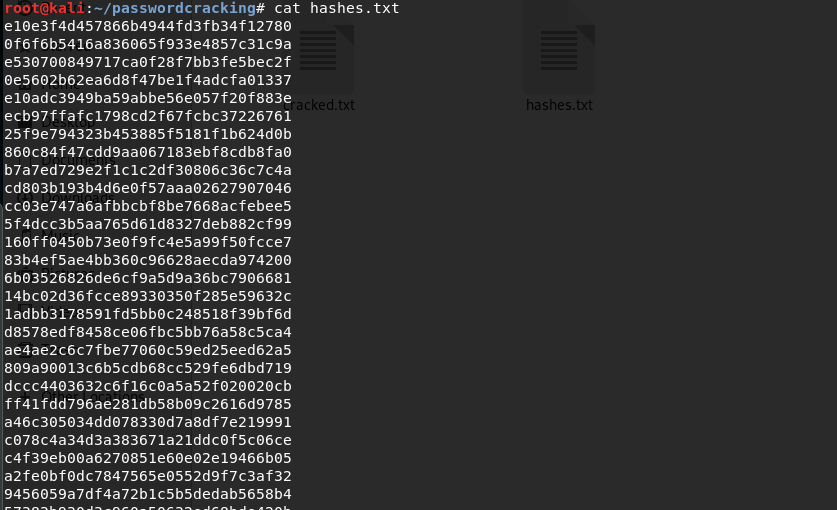

I have downloaded a leaked password database called hak5.txt containing 2351 passwords and converted all the passwords to their MD5 hashes for the sake of this exercise. This means that these are real passwords that real people have used, which is significant because it puts into perspective how weak passwords in real life actually are. This is the file containing the hashes, ‘hashes.txt’:

There are a lot of ways of cracking hashes. But for this demonstration, we will use three of some of the most used cracking techniques: Brute force attacks, Dictionary attacks and Rule-based Dictionary attacks. In general, there is only one approach to cracking a hash: keep guessing strings and compare their hashes with the hashes to be cracked. The different techniques are merely ways of guessing strings.

1. Brute force attack:

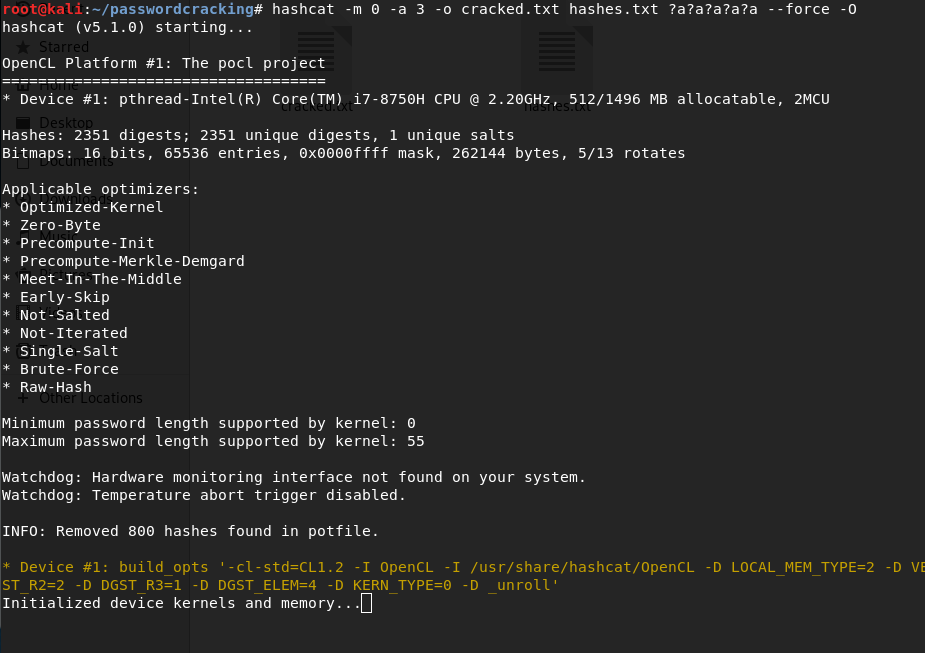

This is a naive approach but it works surprisingly well. We basically guess every combination of characters of every length, hash each one of them and compare. At some point, the hashes match and we have the password. This, however, is only practical for passwords of small length since the number of combinations to guess goes exponentially higher as the length of the string increases. Below is an example of a brute force attack:

Command: $ hashcat -m 0 -o <output_file> <hashes> <guess_params> --force -O

Running the Command:

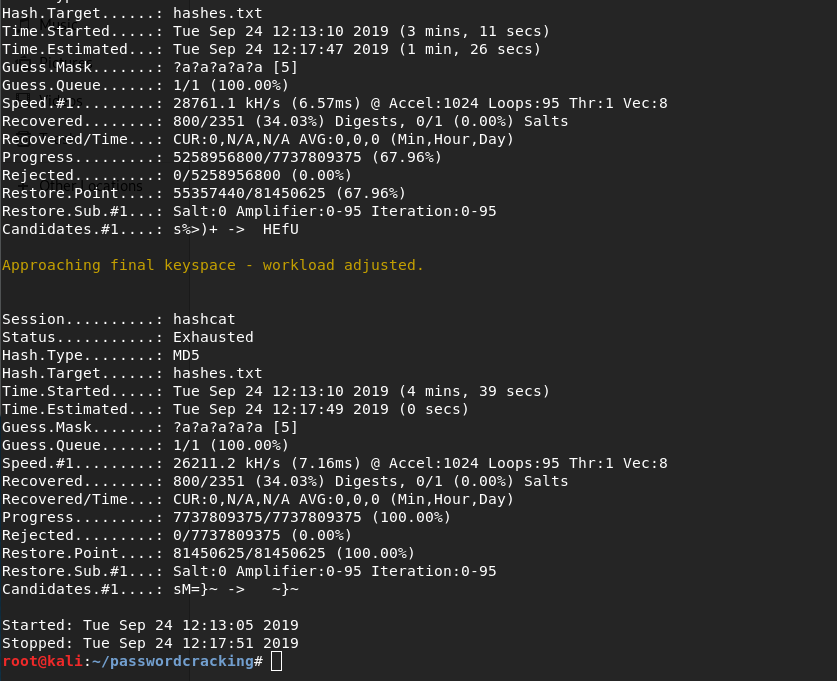

Stats after completion:

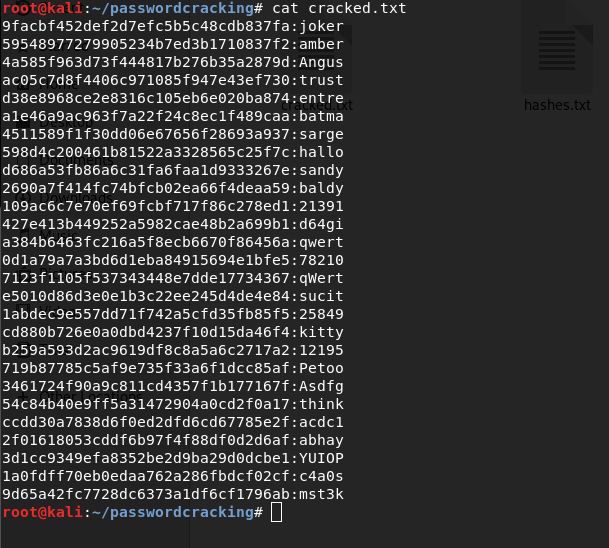

Cracked Passwords:

So let’s go about this process step by step:

First, the command:

hashcatis the program that we’re using.-m 0tells the program that the hash that we want to crack is md5.-a 3tells the program that the attack type is brute force.-o cracked.txtsends all the cracked passwords to a file with name cracked.txt.hashes.txtis the file containing the md5 hashes.?a?a?a?a?ais the main thing here: It tells hashcat to guess strings of length exactly 5 and containing lowercase alphabets, uppercase alphabets and digits.--forceand-Oare device specific options to override some driver issues.

After the process is done, we check the contents of the file cracked.txt. We see that there were a good amount of passwords of length 5 and containing only alphanumeric characters.

The more important aspect to consider is that the process took 4 mins and 39 seconds, which is pretty fast considering the fact that the machine needs to hash and check every possible alphanumeric string of five characters. But any password length greater than seven or eight characters would need days to crack. So this technique is highly impractical for longer passwords.

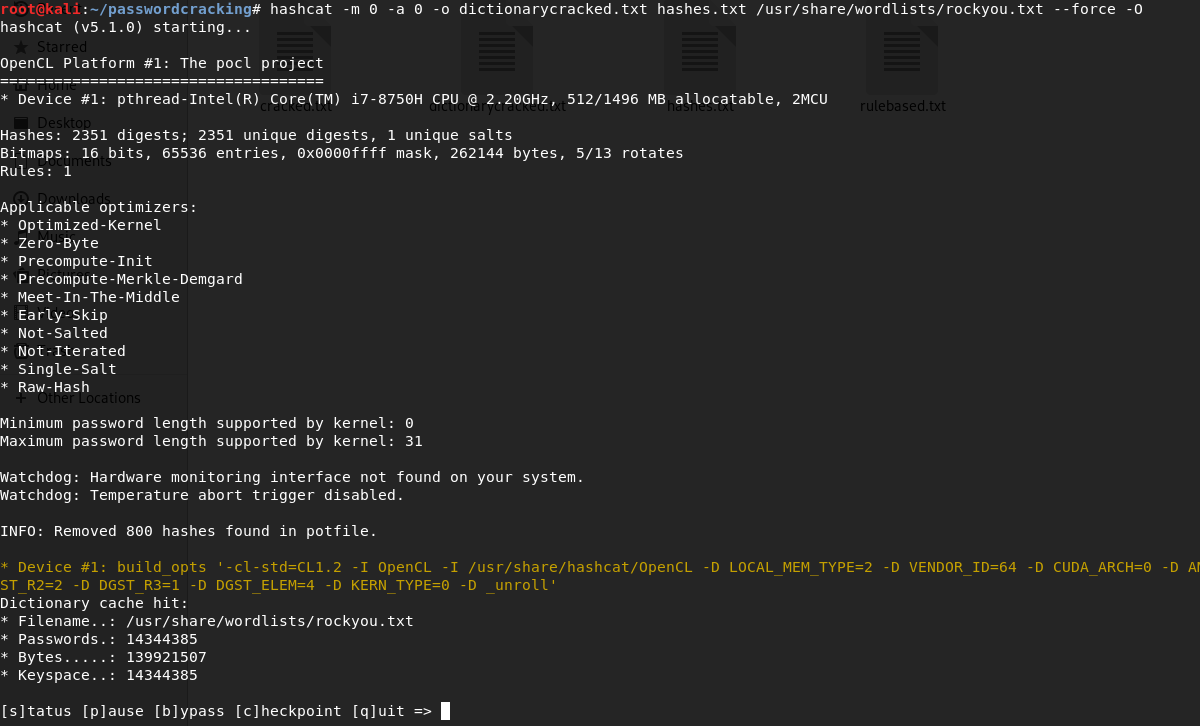

2. Dictionary attack:

The bigger problem with brute force is that most of the strings it guesses are very random. An average user would never think of keeping something like ‘hSN3Lp67sUe’ as their password since it is hard to remember. So, most of the passwords that are guessed in brute force attacks are pretty much useless and a waste of time. To eliminate this problem, we use dictionary attacks. Instead of trying every possible combination, we guess strings that are most likely to succeed. This is done using ‘wordlists’ or ‘dictionaries’. These are files containing common passwords obtained from online password leaks. We consider these strings as the basis of our guesses. We first check the existing strings in the wordlist and then small variations of them (Like converting them to uppercase or adding a period in between). Let me demonstrate:

Command: $ hashcat -m 0 -o <output_file> <hashes> <path_to_wordlist> --force -O

Running the Command:

Stats after completion:

Cracked Passwords:

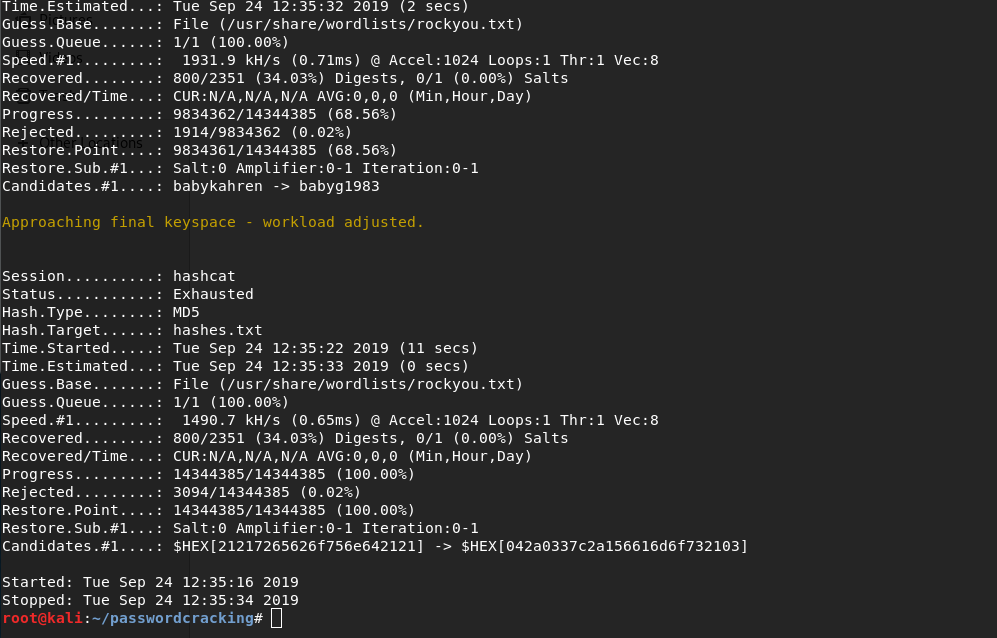

This time, we get a lot more passwords. Everything in the command remains the same except we change the attack type from 3 to 0 to denote dictionary attack and specify the path to the wordlist, which, in this case is rockyou.txt. Certain points to note:

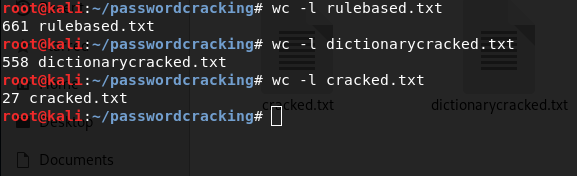

We get a lot more passwords than brute force. On counting, we find that we have cracked 558 passwords with the dictionary attack which is massive compared to the 27 passwords that we cracked using brute force.

The more important thing to note is that the time taken is just 11 seconds which is a phenomenal improvement over brute force. So, the number of passwords cracked per second is much higher in a dictionary attack.

There is only one downside to basic dictionary attacks: the wordlist has to be really good. The success of a dictionary attack depends heavily on the wordlist used.

Let us take this one step further. Though we obtained 558 passwords with dictionary, there are over 2000 hashes in the hashes.txt file. So we need a way to crack more passwords.

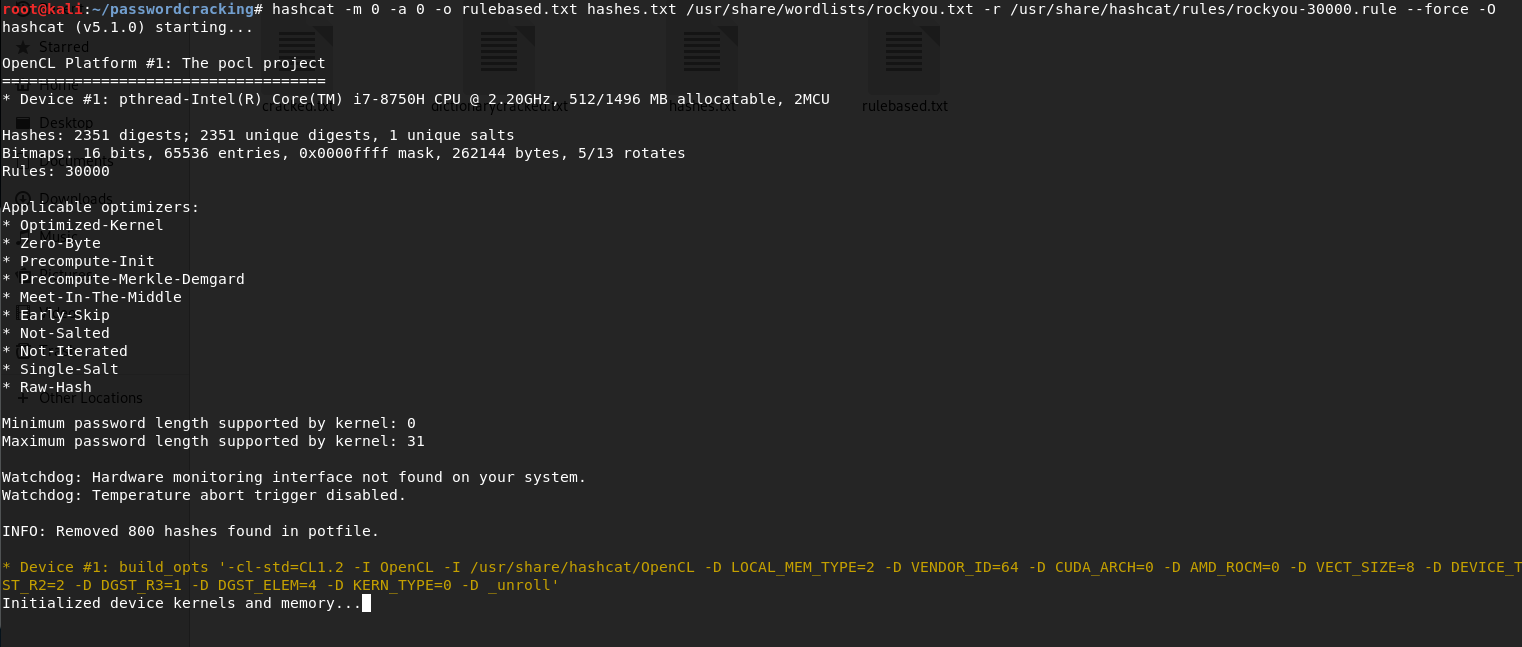

3. Rule-based Dictionary attacks:

When we usually think of guessing someone’s password, we usually think about the most common passwords like ‘password’ and then we try to perform variations on that like ‘p@$$word’ or ‘PaSsWoRd’ or ‘wordpass123’. Though dictionary attacks can check some of these variations, they don’t go far enough since they are programmed to check for common things like adding a period somewhere in between the string or substituting spaces with underscore. To really exhaust all the possible variations, we can write custom rulesets based on which the program can check for a huge number of variations on every string in a wordlist. To demonstrate:

Command: $ hashcat -m 0 -o <output_file> <hashes> <path_to_wordlist> -r <path_to_ruleset> --force -O

Running the Command:

Stats at the end of execution:

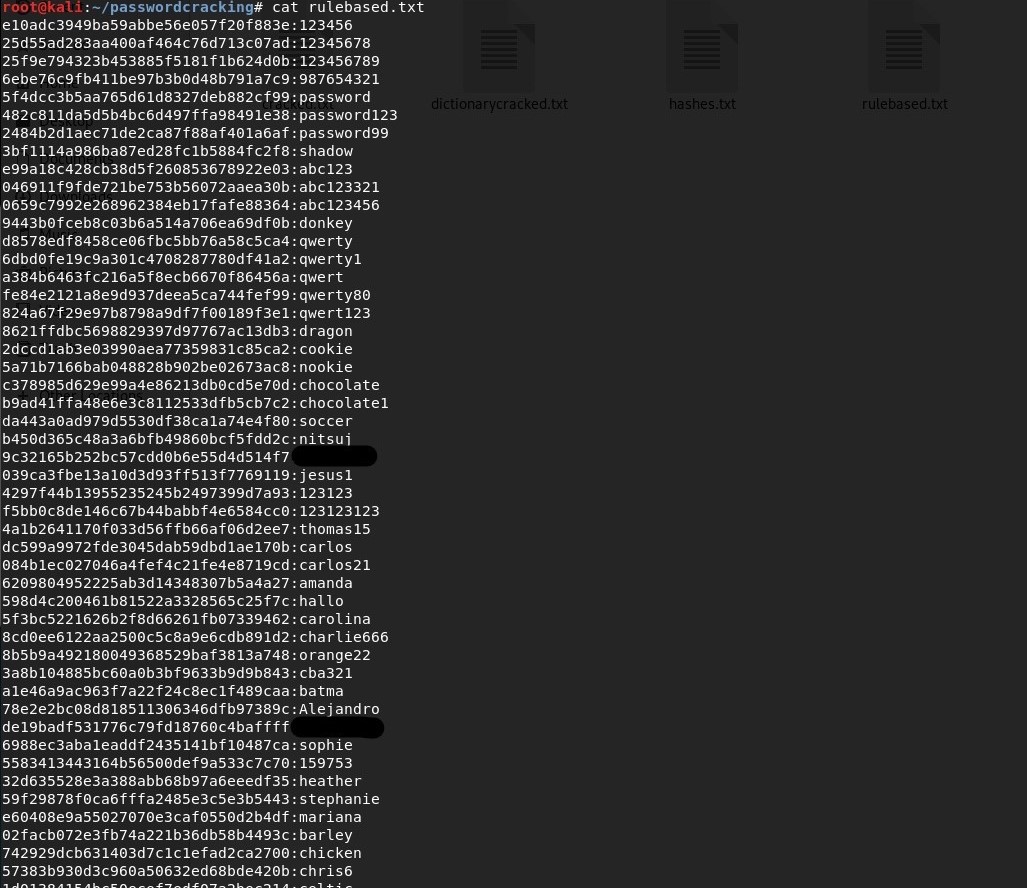

Cracked Passwords:

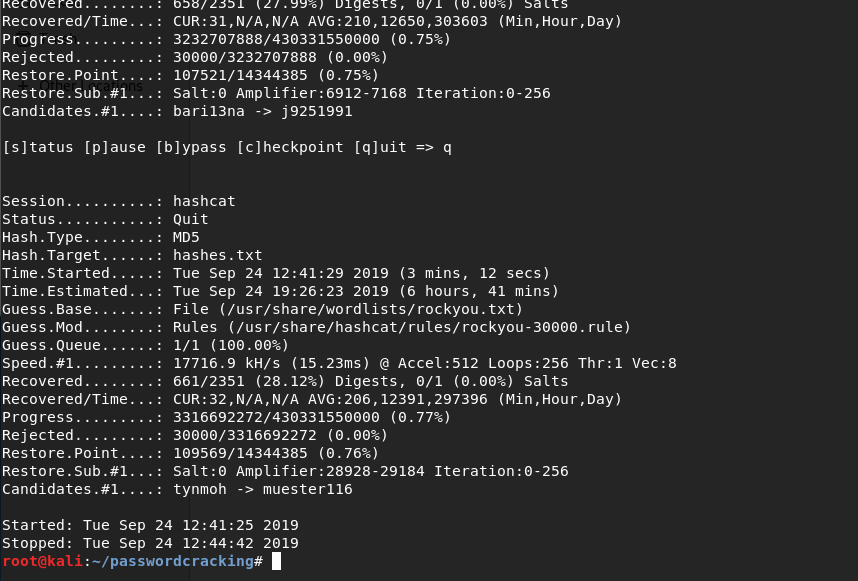

I terminated the process at 0.77% completion. It would take hours for hashcat to complete the process with the computing power that my computer can provide. Let me put up an image to compare how many passwords we have obtained with each technique:

The differences between the techniques are apparent. Even though the rule-based attack completed only 0.77% of its procedure, it got more passwords than basic dictionary attack which completed 100% of its procedure. This should put into perspective how powerful rule-based dictionary attacks are, while being sufficiently fast.

In terms of the command, everything remains same except that we include a ruleset with -r \<pathtoruleset\>. With a enough of computing power, it is possible to crack almost all hashes in the hashes.txt file in minutes.

There are many more password cracking techniques like rainbow table attacks, combinator attacks, etc, but they work on similar principles while being slightly faster.

While we only cracked md5 hashes, these techniques remain same for every other hashing algorithm with the only difference being changes in computation time for each hash operation depending on the hashing algorithm used.

So, now we have proved that just hashing won’t make the passwords secure. Then what is the best way of storing passwords?

The Best we can do: Hashing and Salting, Hash Stretching

Conventionally, we store just the hash of the password in the database. This has one major problem: Same passwords don’t have different hashes. This is called determinism. Using salting, we can give an illusion of non-determinism.

If the password is ‘password’, it can be converted into it’s MD5 hash and stored as ‘5f4dcc3b5aa765d61d8327deb882cf99’ in the database. This can easily be cracked with either a basic or a rule based dictionary attack. To prevent this, we ‘salt’ the original password, that is, we add some random characters at the end or the beginning of the original password like ‘passwordjUIGhs2g7ah’. The hash of this salted password ‘6610878e2c3fd864fd47a72a677fec4b’ is stored in the database. The salt would vary from user to user. During authentication, the salt for the particular user would be appended to the password input, hashed and then checked with the hash in the database.

Now, this hash is impossible to brute force since the length of the string is pretty huge. It is borderline impossible to crack it using basic or rule based dictionary attack it since the salt is completely random. The only scenario where this password would be compromised is if the attacker miraculously finds the salt for a particular user and performs a rule based dictionary attack with the rule being every guess has the salt appended to the end of it. Even in this scenario, he can only crack one password since different users have different salts.

There is another possibility for attacking salted passwords. With enough computing power, one could technically perform a rule based dictionary attack in combination with a brute force attack. Basically for every guess made by the rule based dictionary attack, represented by, ‘pwd’, we brute force strings, represented by ‘slt’. We then append pwd and slt to obtain a string which is then hashed and checked.

It sure sounds complicated. But anybody having a decent number of GPUs can do these operations fairly quickly. And this eliminates the problem that the attacker had with different users having different salts since whatever strings he generates are random anyway. So how can we make something truly impossible to crack?

We can’t. The only thing that we can do is slow the attacker down. We use a technique called hash stretching to achieve this. Instead of hashing the salted passwords just once, we run it through a loop and repeatedly hash it thousands of times.

This has a lot of advantages. Firstly, with normal hashing, as we have seen, when a good number of passwords are stolen from a web server, and stored offline, it becomes very easy to crack. This is because the attacker has no limit on the number of guesses he can make to get the password. With a sufficiently powerful GPU setup the attacker has the ability to generate billions of guesses per second. Unless a user has a really good password, the attacker would be successful in cracking almost everything that he stole from the server. Hash stretching slows down this process considerably, since for each guess, the machine has to perform the hash algorithm multiple number of times. So, the speed of cracking goes down from billions of passwords per second to a few million, which is a huge difference.

A lot of things have to go right for an attacker to crack a salted password stored after hash stretching. So this is generally agreed as the best way to store passwords. But every organization cannot afford to allocate so many resources for this. Most organizations just stick with whatever they have even though it is obsolete. These outdated systems are what black hats target and exploit. This what happened to Adobe in 2013. They stored their passwords in an encrypted form with every password having the same key. This central point of failure led to around 150 million passwords being compromised.

If an organisation cannot afford to spend enough resources to store passwords securely, they can avail the services of bigger companies like Google or Facebook to handle all authentication. This would be the most secure and cost effective way.

In conclusion, it’s tricky business to store passwords. So either one should not do it or do it properly since password leaks basically strengthen password cracking dictionaries and wordlists. Every compromised password grants extra power to malicious hackers. Hence it is very important to store passwords securely.

References:

-

https://auth0.com/blog/adding-salt-to-hashing-a-better-way-to-store-passwords/

-

For anyone interested, I’ve uploaded the ‘hashes.txt’ file to a github repo. So if you want to try these exercises out yourself, feel free to do so. Repo link : https://github.com/suhasks123/hak5-MD5-Hashes

-

https://laconicwolf.com/2018/09/29/hashcat-tutorial-the-basics-of-cracking-passwords-with-hashcat/