Organic Photovoltaics

Introduction :

Photovoltaics is the process of directly converting sunlight into electricity without any heat engine to interfere. Photovoltaic devices are rugged and simple in design requiring very little maintenance and their biggest advantage being their construction as stand-alone systems to give outputs from microwatts to megawatts. Hence they are used for a vast array of applications resulting in the increase in demand for photovoltaics. Recently, ORGANIC PHOTOVOLTAICS (OPV), has been the subject of active research as this technology has the potential to spawn a new generation of low-cost, solar-powered products with thin and flexible form factors.

Solar Technology :

Solar technologies are currently dominated by wafer-size single-junction solar cells based on crystalline silicon that are assembled into large area modules. However, other semiconductor materials and devices are under active investigation in order to further reduce the cost of produced electricity by increasing the power conversion efficiency, reducing the amount of absorbing material needed, and lowering the assembly cost of modules. Thin-film photovoltaic technologies, referred to as second-generation photovoltaics, are based on inorganic semiconductor materials that are more absorbing than crystalline silicon and can be processed directly onto large area substrates. Despite the laboratory demonstration of cells with high efficiencies (19+ACU- for CIGS and 16+ACU- for CdTe), the controlled manufacturing of second-generation cells remains a challenge and their commercial use is growing but not as widespread yet.

The advent of Organic Photovoltaics (OPV) :

Over the past two decades, the science and engineering of organic semiconducting materials have advanced very rapidly, leading to the demonstration and optimization of a range of organics-based solid-state devices, including organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), field-effect transistors, photodiodes, and photovoltaic cells. Seeded in the 1960s, fundamental studies on the optical and electronic properties of model organic molecules such as acenes- molecules based on up to five fused benzene rings -this area of research gained significant momentum when high-purity small organic molecules with tailored structure and properties were synthesized and processed at room temperature into thin films using physical vapor deposition techniques.

The low-temperature processing of either organic small molecules from the vapor phase or polymers from solution confers organic semiconductors with a critical advantage over their inorganic counterparts, as the high-temperature processing requirements of the latter limit the range of substrates on which they can be deposited.

Third Generation Technologies :

The organics-based approaches and those that do not rely on conventional single p+AJY-n junctions are often referred to as third-generation technologies. They include: (i) the dye-sensitized solar cells which are electrochemical cells that require an electrolyte+ADs- (ii) multijunction cells fabricated from group IV and III+AJY-V semiconductors+ADs- (iii) hybrid approaches in which inorganic quantum dots are doped into a semiconducting polymer matrix or by combining nanostructured inorganic semiconductors such as TiO2 with organic materials+ADs- (iv) all-organic solid-state approaches.

What is different in OPV?

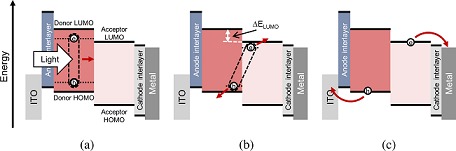

A key difference in the physics of organic semiconductors compared to their inorganic counterparts is the nature of the optically excited states. The absorption of a photon in organic materials leads to the formation of an exciton, i.e., a bound electron-hole pair. The exciton binding energy is typically large, on the order of or larger than 500 meV such binding energies represent twenty times or more the thermal energy at room temperature, kT(300 K) +AD0- 26 meV to be compared with a few meV in the case of inorganic semiconductors. Consequently, optical absorption in organic materials does not lead directly to free electron and hole carriers that could readily generate an electrical current. Instead, to generate a current, the excitons must first dissociate. The excitonic character of their optical properties is a signature feature of organic semiconductors, which has impacted the design and geometry of organic photovoltaic devices for the past decades.

Organic Photovoltaic Devices :

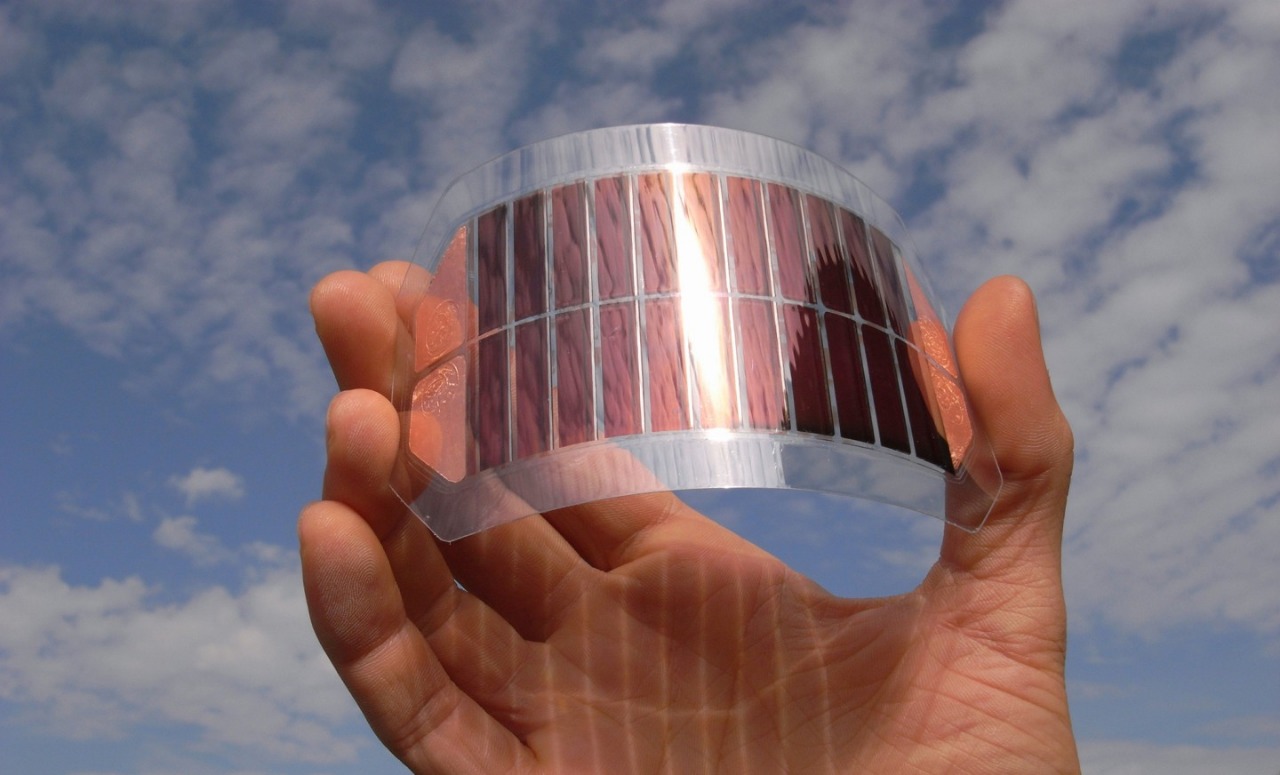

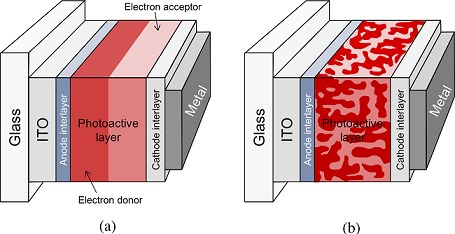

A typical OPV has a layered structure involving: a substrate, a transparent bottom electrode, photoactive layer and top metal electrode. Light is converted to electrical current in the photoactive layer, which has a typical thickness of +AH4- 100 nm. In efficient OPVs, this layer is a composite of two or more semiconductors (electron donors and acceptors) mixed together to form a nanostructured (or bulk) heterojunction for charge generation.

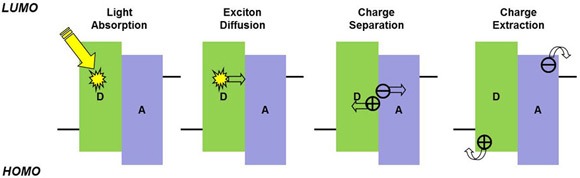

Photocurrent generation in OPVs is a multistep process that can be summarised as follows. Initially, photon absorption by a molecule in the active layer promotes an electron to an excited state, resulting in a localized and tightly bound electron-hole pair (a so-called molecular exciton). To contribute to the photocurrent from the solar cell, the exciton must be dissociated, which requires the Coulomb interaction between the hole and electron (+AH4- 0.5 eV) to be overcome. This step can occur at an interface between electron accepting and donating semiconductors, resulting in the transient formation of a charge-transfer state whereby the electron and hole exist on different molecules. The dissociation of the charge-transfer state is then followed by (1) charge transport - where electrons and holes +ACYAIw-39+ADs-hop+ACYAIw-39+ADs- between adjacent electron acceptor and donor molecules respectively +AJY- and (2) charge extraction at the electrodes of the solar cell. For efficient overall performance, all of these steps should be well characterized and carefully optimized.

Advantages of Organic photovoltaics :

The primary advantage of OPV technology over inorganic counterparts is its ability to be utilized in large areas and semi-transparent, flexible solar modules. Additionally, the manufacturing cost can be reduced for organic solar cells due to their lower cost compared to silicon-based materials and the ease of device manufacturing. The OPVs also offer low thermal budget, solution processing and a very high speed of processing.

Conclusion :

The future of organic solar cells as a pervasive technology for portable power will largely rely on their economic potential. This depends on a number of intricate factors such as efficiency, manufacturing cost, lifetime, form factor, weight, scalability, and sustainable manufacturing.

To summarize, organic photovoltaics provides an exciting playground at the frontiers of science, engineering, and technology. Advances in the near term are likely to lead to solar cells with efficiencies close to 10+ACU- in single heterojunction geometries and efficiencies up to 15+ACU- in tandem-cell geometries. If organic photovoltaics holds its promise, it can soon become a ubiquitous, clean and sustainable technology for portable power and potentially provide large-scale energy production for future generations.