MISSILE HOMING SYSTEMS

INTRODUCTION

When we think about modern-day warfare, we mostly see missiles flying everywhere. In action Hollywood movies, we see the protagonists dodge heat-seeking missiles and fire an RPG at the antagonist to win the battle. We often see the case where these missiles can tail or rather chase an enemy aircraft or tank and reach their target destination accurately, but how does that happen? This is where homing missiles come into the picture.

A homing missile was a particular type of missile. The term was used to describe many types of weapons, including brilliant missiles and many types of concussion missiles, as it simply designated a guided missile. Homing missiles are those missiles Homing missiles have played an increasingly important role in warfare since the end of World War II. In contrast to inertially guided long-range ballistic missiles, homing missiles guide themselves to intercept targets that can maneuver unpredictably, such as enemy aircraft or anti-ship cruise missiles. Intercepting such threats requires an ability to sense the target location in real-time and respond rapidly to changes so that a target intercept can occur.

There are different ways a missile can be guided, and through years of research, trial and error, five basic guidance methods came to be used, either alone or in combination:

- command

- inertial

- active

- semiactive

- passive. Lets us now look into each one of them separately

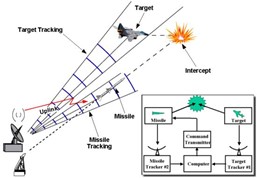

Command Guidance

Command guidance involved tracking the projectile from the launch site or platform and transmitting commands by radio, radar, or laser impulses or along thin wires or optical fibers. Tracking might be accomplished by radar or optical instruments from the launch site or by radar or television imagery relayed from the missile.

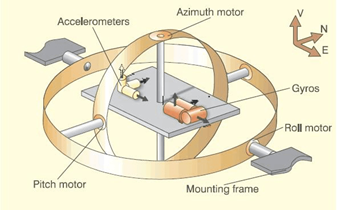

Inertial Guidance

Inertial guidance was first used in long-range ballistic missiles in the 1950s, but it became more popular in tactical weapons after the 1970s, thanks to developments in miniaturized circuits, microcomputers, and inertial sensors. Inertial systems involved using small, highly accurate gyroscopic platforms to continuously determine the missile’s position in space. These served as inputs to guidance processors, which calculated velocity and direction using the location data and inputs from accelerometers or integrating circuits. The flight path was programmed into the guidance computer, which then issued directives to keep the plane on course.

Active guidance

The missile would track its target with active guidance by emitting emissions that it created. For terminal homing, active guidance was extensively utilized. For example, self-contained radar systems were employed to track anti-ship, surface-to-air, and air-to-air missiles. The downside of active guidance is that it relies on emissions that can be traced, blocked, or fooled by decoys.

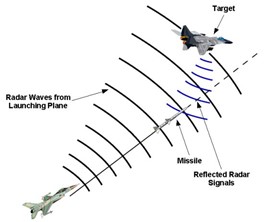

Semi-Active Guidance

Semiactive guidance involved illuminating or designating the target with energy emitted from a source other than the missile; a seeker in the projectile that was sensitive to the reflected energy then homed onto the target. Like active guidance, semiactive guidance was commonly used for terminal homing.

Passive guidance

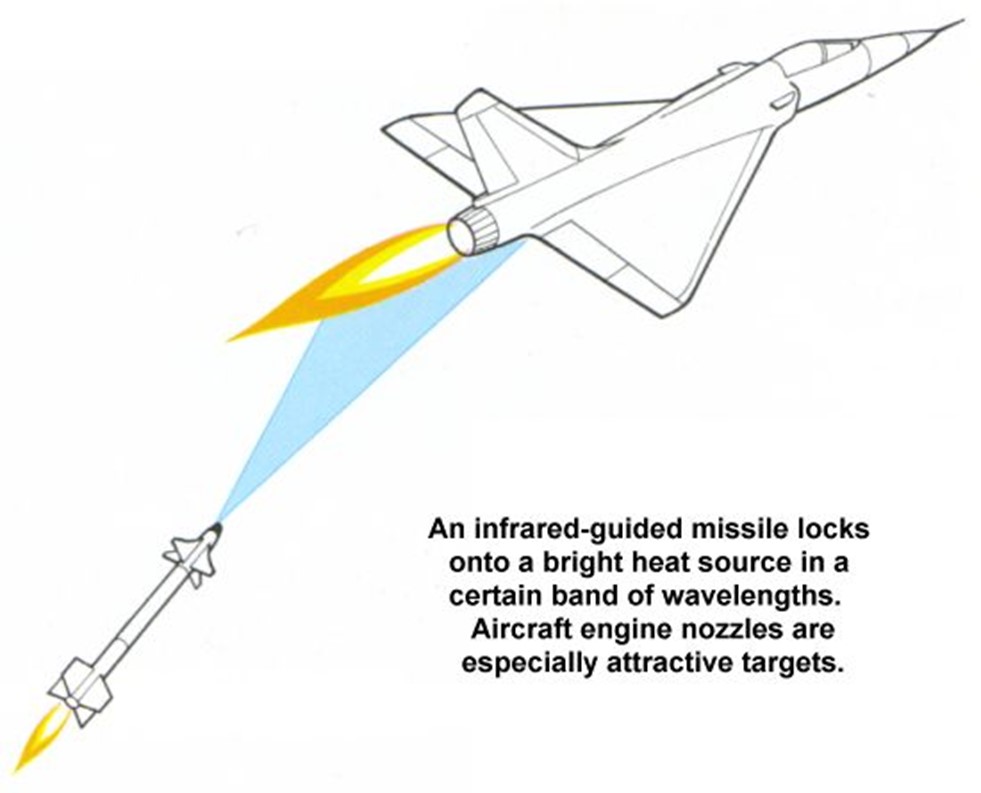

Passive guidance systems neither emitted energy nor received commands from an external source; rather, they “locked” onto an electronic emission coming from the target itself. The earliest successful passive homing munitions were “heat-seeking” air-to-air missiles that homed onto the infrared emissions of jet engine exhausts.

In the present day world and warfare, the primary focus is to develop passive homing systems. Why so? Well, it is so much more convenient for the pilot or soldier operating it to let the computer decide where and when to go and how to attack the enemy while you sit back and just watch the missile hit the target. Passive homing systems are also more accurate in comparison to other homing systems. There are multiple passive homing systems such as ARM ( Anti-Radiation Missiles) and Heat Seeking Missiles.

ARM (ANTI-RADIATION MISSILE) :

INTRODUCTION:

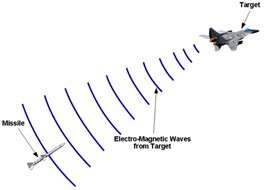

Anti-radiation missiles are used to detect the source of radio emissions from an enemy. The majority of these are made to be used against hostile radar. These missiles are meant to detect and track a radio emission source from an enemy. Typically, these are designed to be used against an enemy radar, but they can also be used to target jammers and even communications radios.

Radar, which stands for radio detection and ranging, was one of the most important inventions of the twentieth century. In the military context, radar allowed for increased communication across the conflict zone and for tracking enemy and non-enemy weapons, planes, boats, submarines, and more. The objective with which these missiles are designed is to break the enemy defence during the first leg of the battle so that the chances of surviving the further waves by the strike aircraft could be doubled.

WORKING:

A traditional anti-radiation missile is attracted to the radar’s mainlobe emission and its horizontal sidelobes and backlobes emission, depending on the distance between the radar and the missile. However, in the case of older radars, the primary target is their extremely high-level horizontal sidelobes and backlobes, which emit continuously. This permits the missile to maintain continuous radar tracking and prevents the passive anti-radiation homing receiver from becoming saturated. Modern radars with very low horizontal sidelobes and backlobes emissions provide a “blinking” target for missiles, with the “blinking” caused by the pauses in receiving the radar mainlobe emission as the antenna rotates.

In this case, missiles without GPS are obliged to estimate the position of the radar-based on an occasionally received emission. The guidance system of the missile is supported by its inertial system when the antenna turn speed is low (long intervals in receiving the emission), especially during the final phase of flight, which often results in a more significant margin of error (a few meters) in detecting the position of the radar than was assumed beforehand.

Missiles without GPS are forced to approximate the position of the radar-based on a rarely received emission in this circumstance. When the antenna turn speed is low (long intervals in receiving the emission), especially during the final phase of flight, the missile’s guidance system is supported by its inertial system, which often results in a larger margin of error (a few metres) in detecting the position of the radar than was assumed beforehand.

INFRARED HOMING

Infrared homing refers to a passive missile guidance system that uses the emission from a target of electromagnetic radiation in the infrared part of the spectrum to track and follow it. Missiles that use infrared seeking are often called “heat-seekers”, since infrared (IR) is just below the visible spectrum of light in frequency and is radiated strongly by hot bodies. Many objects such as people, vehicle engines, and aircraft generate and retain heat and are especially visible in the infra-red wavelengths of light compared to objects in the background.

The infrared sensor package on the tip or head of a heat-seeking missile is known as the seeker’s head. The NATO brevity code for an air-to-air infrared-guided missile launch is Fox Two.

SEEKER TYPES

The three main materials used in the infrared sensor are lead(II) sulfide (PbS), indium antimonide (InSb), and mercury cadmium telluride (HgCdTe). Older sensors tend to use PbS; newer sensors use InSb or HgCdTe. All perform better when cooled, as they are both more sensitive and able to detect cooler objects. Early infrared seekers were particularly successful in detecting shorter wavelength infrared radiation, such as the 4.2-micrometer emissions of a jet engine’s carbon dioxide outflow. Single-color seekers are now used to describe such seekers, which are particularly sensitive in the 3 to 5 micrometer range. Modern infrared seekers also function in the wavelength range of 8 to 13 micrometers, which is the least absorbed by the environment. Two-color systems are a type of seeker. Flares and other countermeasures are less effective against two-color seekers.

SCANNING PATTERNS AND MODULATION

The way by which the space in front of a missile is examined for targets can also determine a missile’s resistance to decoys. Early missiles employed spin scanning, while later seekers used conical scanning, which improves decoy discrimination and overall sensitivity for longer-range tracking. There have also been missiles developed employing rosette scanning techniques. Modern heat-seeking missiles use imaging infrared (IIR), in which the IR/UV sensor is a focal plane array that can “see” in infrared, similar to a digital camera’s CCD. This necessitates a lot more signal processing, but it can be a lot more accurate and difficult to deceive with decoys. In addition to being more flare-resistant, newer seekers are also less likely to be fooled into locking onto the sun, another common trick for avoiding heat-seeking missiles.

Prior to imaging infrared sensors, there was also the issue of sensor modulation; earlier seekers used amplitude modulation (AM) to determine how far off-center the target was and thus how hard the missile had to turn to centre it, but this resulted in increased error as the missile approached the target and the target’s image became relatively larger, which led to increased error as the missile approached the target and the target’s image became relatively larger (creating an artificially stronger signal). This problem was rectified by switching to frequency modulation (FM), which is better able to identify distance without being confused by image size.