Lately, you must been hearing a lot about quantum computing. There are loads of news stories about how it “could change the world” and “open new dimensions”. Universities are hyping up their quantum microchip prototypes, demonstrations of quantum mechanical ideas in silicon, and other devices and theories. But how does it work? What does it do? Who’s doing it? Read this article to find out!

Even though they may be fragile today as well as they need to be kept at temperatures close to absolute zero, Quantum computers aren’t much like the desktop PCs we’re all so familiar with—they’re a whole new kind of machine, capable of calculations so complex, it’s like upgrading from black-and-white to a full color spectrum.

Currently we’re in the midst of entering a new era of quantum computing called the NISQ era, for Noisy, Intermediate-Scale quantum computer as John Preskill, a CalTech theoretical physicist calls it. Quantum computing is more or less in the era that classical computing was in the ‘50s, when room-sized hulks ran on vacuum tubes. But it could potentially revolutionize computing.

Let’s first understand the mathematical theory of quantum mechanics.

When one thing is two things at the same time

In our universe, we are used to a thing being one thing. A coin, for example, can be heads, or it can be tails. But if the coin followed the rules of quantum mechanics, the coin would be flipping midair.(Amazing right?) So until it lands and we look at it, we don’t know if it’s heads or tails. Effectively, it’s both heads and tails at the same time.

We do know one thing about this coin. There is a probability for the flipping coin to be either heads or tails. So the coin isn’t heads, it’s not tails, it’s—for example—the probability of 20% heads and 80% tails. Scientifically speaking, how can a physical thing be like this? How do we even begin describe it?

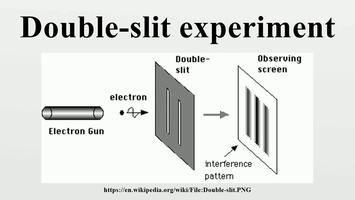

The most mind-boggling part of quantum mechanics is that for some reason, particles like electrons seem to act like waves, and light waves like particles. Particles have a wavelength. The most basic experiment demonstrating this fact is the double slit experiment:

If you put a pair of parallel slits in a partition between a beam of particles and a wall, and put a detector on the wall to see what happens, a strange pattern of stripes appear. It’s called an interference pattern.

Like waves, the particles-waves that travel through one slit interfere with those that travel through the other slit. If the peak of the wave aligns with a trough, the particles cancel out and nothing shows up. If the peak aligns with another peak, the signal in the detector would be even brighter. (This interference pattern still exists even if you only send one electron at a time.) If we were to describe one of these wave-like particles (before they hit the wall) as a mathematical equation, it would look like the mathematical equation describing our coin (before it hits the ground and lands on heads or tails).

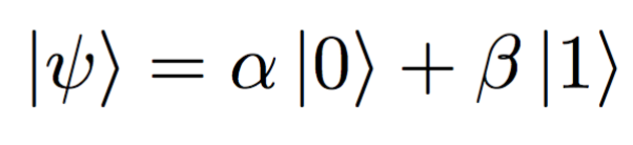

These equations can look kind of scary, like this:

But all you need to know is that this equation lists the particle’s definite properties but doesn’t say which one you’ll get. You can use this equation to find the probabilities of some of the particle’s properties. And because this math involves complex numbers—those containing the square root of i —it doesn’t just describe the probability of a coin being heads or tails, it describes an advanced probability, which could include the way the face of the coin will be rotated.

From all this crazy math, we get a couple of crazy things:

1. There is superposition—the midair coin being heads and tails at the same time.

2. There is interference—probability waves overlapping and canceling each other out.

3. There is entanglement, which is like if we tied a bunch of coins together, changing the probability of certain outcomes because they’re, well, entangled now.

These three phenomenon are exploited by quantum computers to make whole new kinds of algorithms.

“Quantum computers turn the rules of computers on their heads.”

How a quantum computer works

As Martin Laforest, Senior Manager of Scientific Outreach at the Institute for Quantum Computing at the University of Waterloo has said,“In some sense we’ve been doing the same thing for 60 years. The rules we use to compute have not changed—we’re stuck with bits and bytes and logic operations,. But that is all about to change. Quantum computers turn the rules of computers on their heads.”

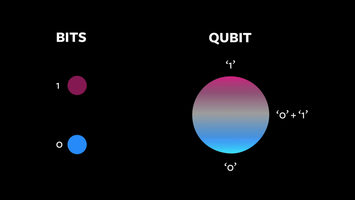

The traditional common digital computing requires that the data be encoded into binary digits(bits), each of which is always in one of two definite states (0 or 1), whereas quantum computation use quantum bits or qubits, which can be in superpositions of states.

The qubit is like a regular bit, but it’s both a zero and a one at the same time (before you look at it). It’s that coin flipping in midair. A quantum computer is like flipping multiple coins at the same time—except while these coins are flipping, they obey the rules of superposition, interference and entanglement.

The quantum computer first bestows the qubits with this quantum mechanical version of probability of what will happen once you actually peep the qubit. (Once you peep the qubit it becomes a defined bit.) Quantum mechanical computations are made by preparing the qubits (or adding weights to a coin before you flip it to manipulate the probability of the outcome), then interacting them together (or flipping a bunch of entangled coins at once) and then measuring them (which causes the coins to stop flipping and produces the final value). If done properly, all of this mid-air interaction should result in a best answer (the value) to whatever question you’ve asked the computer.

Quantum computing algorithms perform calculations by manipulating these qubits via the mathematics of quantum mechanics. At its core, that math is just probability combined with complex numbers and the linear algebra. Quantum computers computes a special version of probabilities—not just heads vs. tails but also the orientation of the coin. So as you throw these coins up in the air, they collide with each other with their different sides and orientations, and this changes the probability of the side revealed by the outcome. Sometimes they bump into each other and cancel each other out, making certain outcomes less likely. Sometimes they push each other along, making certain outcomes more likely. All this is interference behavior and the idea in modeling a quantum computer is to choreograph a pattern of interference so that everything cancels out except for the required answer. To the observer, the answer just looks like the output of regular bits. The quantum mechanics happens in the background.

Quantum Vs Classical:

- Information processing—In a classical computer, bits are processed sequentially, which is similar to the way a person would solve a math problem by hand. In quantum computation, qubits are entangled together, so changing the state of one qubit influences the state of others regardless of their physical distance. This allows quantum computers to intrinsically converge on the right answer to a problem very quickly.

- Interpreting results—In classical computing, only specifically defined results are available, inherently limited by algorithm design. Quantum answers are probabilistic, meaning that because of superposition and entanglement, multiple possible answers are considered in a given computation. Problems are run multiple times, giving a sample of possible answers and increasing confidence in the best answer provided.

- Information representation—In classical computing, a computer runs on bits that have a value of either 0 or 1. Quantum bits, or “qubits,” are similar, in that for practical purposes, we read them as a value of 0 or 1, but they can also hold much more complex information, or even be negative values.

A Physical Orbit:

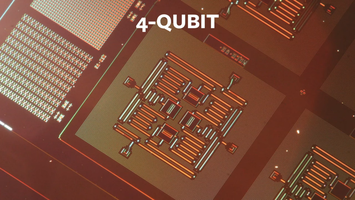

Regular computers were made by scientists using transistors and electrical switches which stores the bits. Similarly, they need hardware that can store a quantum bit. The key to producing a quantum computer is finding a way to model a quantum system that people can actually control—actually set the probabilities and orientations of those flipping coins. This can be done with atoms trapped by lasers, photons, and other systems. But right now, almost everyone in the industry who’s presented a quantum computer has done so with superconductors—ultra-cold pieces of specially-fabricated electronics.

They look like really small microchips. Except these microchips get placed into room-sized refrigerators cooled to temperatures just above absolute zero. These superconducting qubits stay quantum for a long time while performing quantum computing operations.

Actually performing calculations with these qubits can be a challenge. Regular computers have error correction, places where multiple bits perform the same function in case one of them fail. For quantum computers to do this, they need to have extra qubits built into their system specifically to check errors. But the nature of quantum mechanics makes actually doing this error correction more difficult than it does in classical computers. It could take around two thousand physical qubits working in tandem, in fact, to create one reliable “error-corrected” qubit resistant to messing up.

Better qubits and further research continue to bring us closer to the threshold where we can construct few-qubit processors. Now we’re at the junction where the theoretical demand versus the reality of experiments are converging together.

Who’s working on it?

Universities, national labs, and companies like IBM, Google, Microsoft and Intel are pursuing qubits set-ups in logic circuits similar to regular bits, all with less than 20 qubits so far. Companies are simultaneously simulating quantum computers with classical computers, but around 50 qubits is seen as the limit—IBM recently simulated 56 qubits, which took 4.5 terabytes of memory in a classical computer.

A quick look at the progress of the mentioned companies:

-

IBM is taking a long-term approach, hoping to one day release a general-purpose quantum computer that classical computers rely on, when needed, through the cloud. Intel has just entered the race with their 17-qubit processor released in October.

-

Microsoft is working on a different kind of “topological” qubit based on the behaviors of many electrons, and described a similar long-term goal for quantum computing involving scalable hardware.

-

Google has been rumored to unleash a quantum computer that will achieve “quantum supremacy” with 49 or 50 qubits. Quantum supremacy simply means finding one single algorithm for which a quantum computer always win, and for which a classical workaround can’t be found to solve the same problem. In Google’s case, the team will set up a quantum circuit with their qubits by entangling them (essentially, setting up a quantum link between them) and then allowing the system to evolve over time. At the end, how the qubits evolve is set by the rules of quantum mechanics, but the final measurement could take on different values with different probabilities. Figuring out the possible outcomes of the qubits, alongside the probability of measuring the outcomes, is so complex that the classical computer needs to simulate the quantum computer in order to do so, and might take weeks to do what the quantum computer can do in minutes.

-

IonQ,a startup will use atoms trapped by lasers.

-

D-Wave, a longtime quantum computing business uses a specialized system called quantum annealing to perform optimization problems. Rather than just a dozen to a few dozen qubits, D-Wave has announced a computer with 2,000 qubits and rather than rely on quantum logic circuits like the rest of the pack, their computer solves one type of problem—optimization problems, like finding the best solution from a range of okay solutions, or finding the best taxi route from point A to point B staying as far as possible from other taxis. These kind of problems are potentially useful in finance.

The outlook

Everyone agrees that we’re far from seeing quantum computers used in everyday life—there’s a lot of excitement but we’re still in the early days. There are still loads of challenges to overcome, like error correction. Then comes the related problem of transmitting quantum information between distant computers or storing quantum information long term in memory.

While 2017 seems to be a year amidst a sort-of quantum boom, having a consumer-facing quantum computing product is still far off milestone. So no, you cannot own a quantum computer now. You hear about some benefits of quantum computing in the next few years, like biochemical advances, but other advantages could be 20 years down the line but it will definitely be worth the wait!

Some Cool Links to checkout!

Try Your Hand at Quantum Computing