Before plunging into understanding the beauty of the thin shell structures or even knowing whatgwho the candela in the title refers to. Let us imagine a scenario where you’re at an eatery. You pick up a slice of pizza, and you’re about to take a bite. But it flops over and sags about your fingers. Maybe you should have gone for fewer toppings? No really. Enough experience with pizzas has taught us that folding the pizza slice into a U-shape keeps the pizza from flopping over .

Behind this simple intuition there lies a powerful mathematical result about curved surfaces. One that’92s so startling that its discoverer, the mathematical genius Carl Friedrich Gauss, named it Theorema Egregium, Latin for excellent or remarkable theorem. Gauss’s wanted to define curvature in such a way that bending does not affect the curvature. On any surface, let us say spherical , one can trace many paths to come down from the top. Gauss intended to use all these choices into account. Here’s how it works. Starting at any point, find the two most extreme paths that you can choose (i.e. the most concave path and the most convex path). Then multiply the curvature of those paths together (curvature is positive for concave paths, zero for flat paths, and negative for convex paths). The number you get is Gauss’s definition of the curvature at that point.

Let us take the case of a Cylinder, the two extreme paths from any point are namely, a straight path and a completely circular path. Since the straight path has zero curvature, thus the Gaussian curvature of a Cylinder is zero. That’s the reason why engineers say cylinder is flat. Similarly curvature calculations with sphere, we get the Gaussian curvature to be a non zero value.

So spheres are curved while cylinders are flat. You can bend a sheet of paper into a tube, but you can never bend it into a ball. A surprising consequence of this result is that you can take a surface and bend it any way you like, so long as you don’t stretch, shrink or tear it, and the Gaussian curvature stays the same. That’s because bending does not change the distances between any two points. Similarly, have you ever tried gift wrapping any spherical object , let’s say a football(ggmu). No matter how you bend a sheet of paper, it’ll always retain a trace of its original flatness, so you end up with a crinkled mess.

Now back to pizza, initially the pizza was flat, Gaussian curvature was zero. So when the pizza flopped while eating the breadth of the pizza was straight maintaining the Gaussian curvature zero. Now instead by forcing it to bend we are forcing it to become flat in the other direction..Once you recognize this idea, you start seeing it everywhere. By curving a sheet in one direction, you force it to become stiff in the other direction.

Now let us consider the scenario of an egg. Take an egg from your fridge and try to squeeze it by putting your fingers around it. You’ll surprised to see that you can’t. This is due to the fact that egg shells are curved on both sides, thus giving higher rigidity.

Shape for a nuclear power plant cooling tower also incorporates curvature in both directions. This shape, called a hyperboloid, minimizes the amount of material required to build it

Hyperboloid Parabaloid is another shape that uses double curvature. You can look into the infamous punch of a Mantis Shrimp to know more regarding the exceptional strength of this shape.

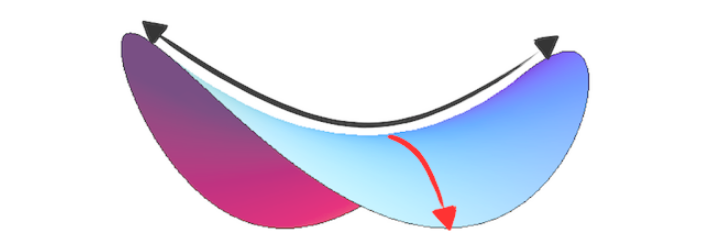

So what makes this Hyperboloid Parabaloid shape so strong? It has to do with how it balances pushes and pulls. All structures have to support weight, and ultimately transfer this weight down to the ground. They can do this in two different ways. There’s compression, where the weight squeezes an object by pushing inwards. An arch is an example of a structure that exists in pure compression. And then there’s tension, where the weight pulls at the ends of an object, stretching it apart. The hyperbolic paraboloid combines the best of both. The concave part is stretched in tension while the convex part is squeezed in compression Through double curvature, this shape strikes a delicate balance between these push and pull forces, allowing it to remain thin yet surprisingly strong.

The strength of this shape was well understood by the Spanish-Mexican Architect and Engineer Felix Candela. He built structures that took the hyperbolic paraboloid shape. When you hear the word concrete, you might think of heavy, boxy constructions. Yet Candela was able to use the hyperbolic paraboloid shape to build huge structures that expressed the incredible thinness that concrete can provide. His lightweight, graceful structures might seem delicate, but in fact they’re immensely strong, and built to last. Felix Candela is one of the greatest structural engineers of the twentieth century. Candelas work demonstrates three ideals which are essential to the education of structural engineers and to anyone with an appreciation for the built environment: Firstly to conserve natural resources by minimizing materials. Secondly , to reduce cost by intelligent design . Lastly creating beautiful structures. His structures were a testimony to all the three ideals.

In the late 1950’s his influence spread across the world and one such country which embraced this type of thin shell structures was Cuba. Cubans have an international reputation for their spirited high-quality art, which is manifested in mediums such as paintings, sculptures, cinema, music, as well as the design of structures. Here are a few of the thin shell structures in and around Havana which came up during the 1950’s in consequence to the famous partnership between Max Borges and Felix Candela.

There was a lot of optimism and hope that permeated Cuba during the forties and fifties. As can be witnessed in these remarkable structures.

But then Castro happened. And left Cuba Crawling. Numb.