Ballistics is the science of the propulsion, flight, and impact of projectiles especially bullets, unguided bombs or rockets. It is divided into several disciplines. Internal and external ballistics, respectively, deal with the propulsion and the flight of projectiles. The transition between these two regimes is called intermediate ballistics. Terminal ballistics concerns the impact of projectiles which is a separate category that study the wounding of personnel

Internal Ballistics

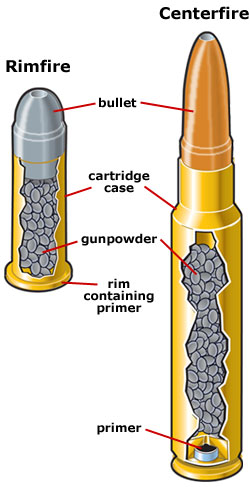

A fire arm cartridge contains four components namely Primer, Case, Propellent and Bullet__. The basic working of a fire arm is that when the trigger is pressed the firing pin of the gun strikes the primer of the cartridge. When the firing pin hit the primer, the primer explodes which will ignite the propellent (In some modern guns electric signals are also used for igniting the powder). The ignition of propellent produce gases which pushes the bullet out of the barrel. In fire arms the internal ballistics deals with the explosion of primer, ignition of the firing till the bullet exits the barrel.

The study of internal ballistics is important in the design of the chamber and barrel of the fire arm. Bullets fired from a rifle will have more energy than similar bullets fired from a handgun. More powder can also be used in rifle cartridges because the bullet chambers can be designed to withstand greater pressures (50,000 to 70,000 for rifles psi vs. 30,000 to 40,000 psi for handgun chamber). Higher pressures require a bigger gun with more recoil that is slower to load and generates more heat that produces more wear on the metal. It is difficult in practice to measure the forces within a gun barrel, but the one easily measured parameter is the velocity with which the bullet exits the barrel (muzzle velocity). The controlled expansion of gases from burning gunpowder generates pressure (force/area). The area here is the base of the bullet (equivalent to diameter of barrel) and is a constant. Therefore, the energy transmitted to the bullet (with a given mass) will depend upon mass times force times the time interval over which the force is applied. The last of these factors is a function of barrel length. Bullet travel through a gun barrel is characterized by increasing acceleration as the expanding gases push on it, but decreasing pressure in the barrel as the gas expands. Up to a point of diminishing pressure, the longer the barrel, the greater the acceleration of the bullet.

The study of internal ballistics is important in the design of the chamber and barrel of the fire arm. Bullets fired from a rifle will have more energy than similar bullets fired from a handgun. More powder can also be used in rifle cartridges because the bullet chambers can be designed to withstand greater pressures (50,000 to 70,000 for rifles psi vs. 30,000 to 40,000 psi for handgun chamber). Higher pressures require a bigger gun with more recoil that is slower to load and generates more heat that produces more wear on the metal. It is difficult in practice to measure the forces within a gun barrel, but the one easily measured parameter is the velocity with which the bullet exits the barrel (muzzle velocity). The controlled expansion of gases from burning gunpowder generates pressure (force/area). The area here is the base of the bullet (equivalent to diameter of barrel) and is a constant. Therefore, the energy transmitted to the bullet (with a given mass) will depend upon mass times force times the time interval over which the force is applied. The last of these factors is a function of barrel length. Bullet travel through a gun barrel is characterized by increasing acceleration as the expanding gases push on it, but decreasing pressure in the barrel as the gas expands. Up to a point of diminishing pressure, the longer the barrel, the greater the acceleration of the bullet.

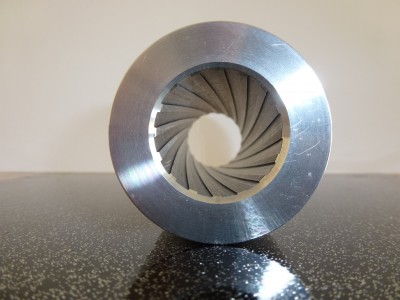

Rifling of barrel

In firearms, rifling is the helical groove pattern that is machined into the internal (bore) surface of a guns barrel, for the purpose of exerting torque and thus imparting a spin to a projectile around its longitudinal axis during shooting. This spin to serves gyroscopically stabilize the projectile by conservation of angular momentum, improving its aerodynamic stability and accuracy over smooth bore designs.

Transitional ballistics

The study of transitional ballistics is used for design of accessories like flash suppressors, sound suppressors and recoil compensators. The study of transitional ballistics is difficult as it involves a number of variables which is not properly defined. When the bullet reaches the muzzle of the barrel, the escaping gases are still, in many cases, at hundreds of atmospheres of pressure. Once the bullet exits the barrel, breaking the seal, the gases are free to move past the bullet and expand in all directions. This expansion is what gives gunfire its explosive sound and is often accompanied by a bright flash as the gases combine with the oxygen in the air and finish combusting.

The propellant gases continue to exert force on the bullet and firearm for a short while after the bullet leaves the barrel. One of the essential elements of accurizing a firearm is to make sure that this force does not disrupt the bullet from its path

External Ballistics

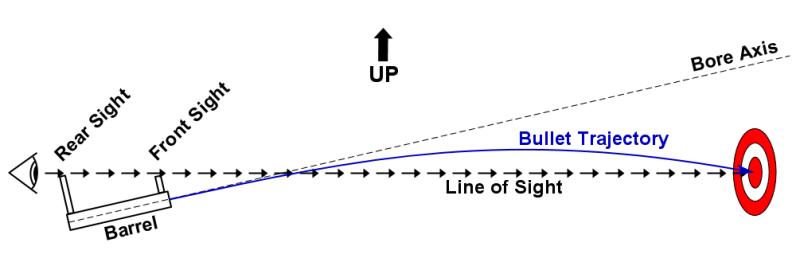

Exterior ballistics deals with that portion of the bullet’s flight from the moment it leaves the muzzle until its impacts. In a handgun, especially a defensive arm, the flight of the bullet is rather short, and the atmosphere and laws of physics have less opportunity to influence things. In a high-powered rifle, these forces have plenty of time to show their effects. To be able to put that bullet precisely on target, you need to fully understand how the bullet will react to your environment at a wide variety of ranges. Entire lifetimes have been spent in pursuit of the accurate prediction of bullet trajectories. While the answers are out there, the science of ballistics is constantly evolving, and our ability to quantify and predict the values associated with the bullet’s path is improving all the time. When in flight, the main forces acting on the projectile are gravity, drag and if present wind. Gravity imparts a downward acceleration on the projectile, causing it to drop from the line of sight. Drag or the air resistance decelerates the projectile with a force proportional to the square of the velocity (or cube, or even higher powers of v, depending on the speed of the projectile). Wind makes the projectile deviate from its trajectory. During flight, gravity, drag and wind have a major impact on the path of the projectile, and must be accounted for when predicting how the projectile will travel.

The maximum practical range of all small arms and especially high-powered sniper rifles depends mainly on the aerodynamic or ballistic efficiency of the spin stabilized projectiles used. Long-range shooters must also collect relevant information to calculate elevation and windage corrections to be able to achieve first shot strikes. The data to calculate these fire control corrections has a long list of variables including:

- Ballistic coefficient of the bullets used

- Height of the sighting components above the rifle bore axis

- The zero range at which the sighting components and rifle combination were sighted in bullet weight

- Actual muzzle velocity (powder temperature affects muzzle velocity, primer ignition is also temperature dependent)

- Range to target

- Supersonic range of the employed gun, cartridge and bullet combination

- Inclination angle in case of uphill/downhill firing

- Target speed and direction.

- Wind speed and direction (main cause for horizontal projectile deflection and generally the hardest ballistic variable to measure and judge correctly. Wind effects can also cause vertical deflection.)

- Air temperature, pressure, altitude and humidity variations (these make up the ambient air density)

- earth's gravity (changes slightly with latitude and altitude).

- Gyroscopic drift (horizontal and vertical plane gyroscopic effect often know as spin drift - induced by the barrels twist direction and twist rate).

- Coriolis effect drift (latitude, direction of fire and hemisphere data dictate this effect).

- Lateral throw-off (dispersion that is caused by mass imbalance in the applied projectile).

- Aerodynamic jump (dispersion that is caused by lateral (wind) impulses activated during free flight at or very near the muzzle).

- The inherent potential accuracy and adjustment range of the sighting components.

- The inherent potential accuracy of the rifle.

- The inherent potential accuracy of the ammunition.

- The inherent potential accuracy of the computer program and other firing control components used to calculate the trajectory.

Terminal ballistics

It deals with the effect of the projectiles on target especially the pattern of wound made by the bullet. That’s why it is also called wound ballistics. Bullets produce tissue damage in three ways.

Laceration and crushing -

Tissue damage through laceration and crushing occurs along the path or “track” through the body that a projectile, or its fragments, may produce. The diameter of the crush injury in tissue is the diameter of the bullet or fragment, up to the long axis.

Cavitation -

A “permanent” cavity is caused by the path (track) of the bullet itself with crushing of tissue, whereas a “temporary” cavity is formed by radial stretching around the bullet track from continued acceleration of the medium (air or tissue) in the wake of the bullet, causing the wound cavity to be stretched outward. For projectiles traveling at low velocity the permanent and temporary cavities are nearly the same, but at high velocity and with bullet yaw the temporary cavity becomes larger.

Shock waves -

Shock waves compress the medium and travel ahead of the bullet, as well as to the sides, but these waves last only a few microseconds and do not cause profound destruction at low velocity. At high velocity, generated shock waves can reach up to 200 atmospheres of pressure. However, bone fracture from cavitation is an extremely rare event. The ballistic pressure wave from distant bullet impact can induce a concussive-like effect in humans, causing acute neurological symptoms.