GENOME EDITING

A genome is an organism’s complete set of DNAs, together with all of its genes. Every genome contains all the data required to create and maintain that organism. In humans, a replica of the whole genome (more than three billion DNA base pairs) is contained in all cells that have a nucleus. Modification to provide desired traits in plants, animals, and microbes used for food began around 10,000 years ago. These changes, in conjunction with natural evolutionary changes, have resulted in common food species that are currently genetically totally different from their ancestors.

GENETIC ENGINEERING

Genetic Engineering may be a form of genetic modification that involves a deliberate and targeted changes in plant or animal gene sequences to impact a selected attribute by making use of the rDNA technology.

GENETIC ENGINEERING TECHNIQUES

Microprojectile Bombardment

Klein and his colleagues discovered, in the 1980s, that naked DNA can be delivered to plant cells by “shooting” them with microscopic pellets to which DNA had been adhered. This is often a crude however, an effective physical technique of DNA delivery, particularly in species like corn, rice, and different cereal grains, which Agrobacterium doesn’t naturally remodel. Several GE plants in industrial production were at first remodeled with the help of microprojectile delivery.

Electroporation

In electroporation, plant protoplasts take up macromolecules from their encompassing fluid, accelerated by electrical impulse. Cells growing in a medium are stripped of their protective walls, leading to protoplasts. Providing known DNA to the protoplast medium, and so applying the electrical pulse briefly destabilizes the cell wall, permitting the DNA to enter the cell. Remodeled cells would then regenerate their cell walls and grow to whole, fertile transgenic plants. Electroporation is restricted by the poor potency of most plant species to regenerate from protoplasts.

Microinjection

The process of microinjection is quite inefficient and extremely labor-intensive compared to alternative techniques. DNA is injected directly into anchored cells. Some proportion of those cells can survive and integrate the injected DNA.

Transposons/Transposable elements

The genes of most plants and a few animal (e.g., insects and fish) species carry transposons, that are short, naturally occurring items of DNA with the flexibility to maneuver from one location to a different one in the within the genome. Barbara McClintock first described such transposable components in corn plants during the 1950s (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 1951). Transposons are investigated extensively in research laboratories, particularly to check cause, and also the mechanics of DNA recombination. However, they need not however been harnessed to deliver novel genetic information to enhance commercial crops.

GENE ETHICS

A gene-editing tool named Crispr-Cas9, that allows us to treat many diseases, has made ethics question graver than ever. This tool behaves like a pair of molecular scissors that can be used very intricately to have an effect on only specific genes, cutting and splicing them to prevent or cure diseases. One widely held opinion is that it’s unethical to use Crispr on the human sperm cell, eggs and embryos because changes can get carried on for generations and present a range of unsought consequences for the humankind. Laboratory analysis has shown Crispr-Cas9 can accidentally alter genes apart from those intended. This means it may disrupt other genes, impairing functions or causing individuals to become susceptible to infections.

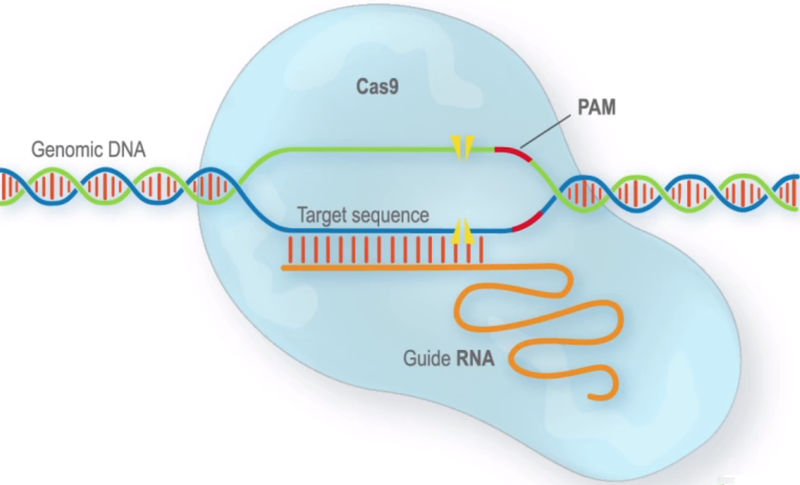

How CRISPR actually works?

CRISPR is a combination of a scissor like protein, such as Cas9, and a guide molecule. The molecule acts like a bloodhound taking CRISPR on the hunt to specific sites within the genome. Once there, the protein cuts the cell’s DNA on the spot. That completely disables the targeted gene. The cells then repair their DNA, they put in a new DNA sequence that the bloodhound also carried, or simply patch up the break caused by CRISPR’s molecular scissors. Enter tiny cellular machines called ribosomes. They translate the edited blueprint, skipping the disease-causing genes or producing healthy proteins that the repaired genes code for. CRISPR’s ability to repair may be most important at the beginning of life. Edit the genome of a very early embryo - one created by in vitro fertilization - and couples who carry disease causing mutations will be able to have children spared from them. Once a child is born with a genetic disease, such as Huntington’s or Tay-Sachs, it is more difficult to use CRISPR to treat it. It’s also being used to research and test treatment for cancer, blindness, and liver diseases among others. But CRISPR isn’t just for humans. Editing the genome of mosquitoes can give us the power to stop spread of diseases like malaria. This opens up a new world of technological advancements. When you can edit the DNA’s blueprint, the possibilities are vast.